Another state of panic

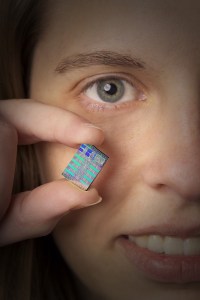

As they were just beginning their work on a second console, the Microsoft team knew how far behind they were compared to Sony. In March 2001, well before Microsoft had shipped the first Xbox, Sony announced its next console would use a Cell microprocessor (pictured right), a new chip with parallel processing features that Sony was jointly designing with Toshiba and IBM.

“I was thinking, ‘Oh my God,'” said one Microsoft staffer as Sony made the announcement. “It scared the shit out of me.”

The Cell was a grand alliance, much like the PowerPC alliance of Apple, Motorola, and IBM — aimed at stopping Intel in the 1990s. The PowerPC effort failed against Intel, but IBM managed to keep it going with new markets, such as game consoles. With Cell, Sony would use the chip in the PlayStation 3, Toshiba would use it in TVs, and IBM would use it in servers. The only weakness, as perceived by Microsoft’s team, was that the Cell would be horribly hard to program.

Since it could take two years to design and make a chip (and longer to make something like the Cell), the Microsoft chip designers had to get started. The chip and hardware strategists were once again in the role of playing catch-up to Sony.

At Microsoft, there wasn’t much time to sit around and take it easy. The engineers got no rest. The WebTV team shipped a satellite digital video recorder called UltimateTV in the fall of 2000. The team was then almost diverted for a time on Freon, a secret project that would have combined the Xbox with UltimateTV. But Microsoft shelved that idea because UltimateTV turned out to be a dud. Microsoft decided to call it quits on the product line in January, 2002.

As it did so, it threw the fate of the WebTV division, based in the Silicon Valley city of Mountain View, Calif., into chaos. Robbie Bach came down to reassure them and offer them jobs in the Xbox hardware operation. Some of the team was assigned to redesigning the Xbox for each year so that it would become cheaper and cheaper to make. Most took the offer, since there was a recession and jobs were scarce elsewhere.

A few of the hardcore WebTV leaders started planning the chips they would use in the next generation Xbox. Those chips were critical, as they had to outdo the competition yet cost a low amount so that the box could be properly cost reduced over time. Two key WebTV engineers, Nick Baker and Jeff Andrews, operated under the code name Project Trinity (named after the female lead character in the sci-fi film The Matrix) and they worked with Xbox architect Mike Abrash.

Earlier in Xbox history, the WebTV team had been spurned by Bill Gates when the rival Xbox team got approval to make a game console, not the WebTV team. Now, they were back as key members of the Xbox team.

“This time, they had a seat at the table,” J Allard, one of the Xbox chiefs, said. “They were full shareholders and citizens on this project. They were on the highest wire with the smallest net.”

Revving up Xbox Live

Revving up Xbox Live

Allard (pictured, right) and his buddy Cameron Ferroni (pictured, left) were busy creating an online gaming service called Xbox Live. Because they had the foresight to put an Ethernet jack, and not a dial-up modem, into the Xbox, they were able to plan a broadband-only network. Sony, by contrast, created both dial-up modem and broadband attachments for the PlayStation 2. That made for slow online games.

On the online front, Robbie Bach could legitimately claim that Microsoft had thought leadership. Microsoft’s vision for Xbox Live went far deeper than anything the rivals were planning. Later, Bach would disclose that Microsoft planned to invest $2 billion in Xbox Live, which would change the game by making it all about innovating with software and services — two areas where Microsoft had an edge on its gaming rivals.

Xbox Live wasn’t ready for the launch of the Xbox. But it would be a major addition to the platform when it went live in the fall of 2002. Always aiming to inspire, Allard told his troops, which he came to call the Tribe over time, “If I needed to pick an introductory quote for the ‘History of the Xbox,’ I’d choose the following words spoken by Gandhi: ‘First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.'”

Veterans and newbies

Veterans and newbies

The team included Xbox veterans who were back for another tour of duty. Robbie Bach was at the top of the management layer as chief Xbox officer, reporting to CEO Steve Ballmer. Todd Holmdahl ran hardware, assisted by Greg Gibson. Marc Whitten ran accessories. Ed Fries ran the game studios.

Allard took on the expanded role of leading the Xbox Platform team, which he described as the team that would create the infrastructure for Disneyland. He was in command of hundreds of people who did everything from the system software to definition of the system.

In January 2002, while much of his team was hard at work on Xbox Live, Allard assigned three people — Mike Abrash, Jeff Henshaw and Margaret Johnson — to explore what Allard called Xbox Next. While that was a good thing to do, this team fell apart in short order.

Cameron Ferroni led Xbox Live and system software. He tapped veterans Jon Thomason, Tracy Sharp, Dinarte Morais and Andrew Goossen as part of a crack team for making system software. Chris Satchell signed up to lead an effort to make better game development tools that made it easy to make both PC and Xbox games simultaneously.

Shane Kim, Stuart Moulder, Ken Lobb, A.J. Redmer (pictured above) and others helped Fries run the game studios. The company also engaged outside development studios such as Lionhead Studios and Epic Games to make exclusives. Thousands of game developers were now inside the Xbox fold. George Peckham ran third-party game publisher relations.

The chain of command could be very deep. Chip experts Nick Baker and Jeff Andrews reported to Larry Yang, the chip chief who in turn reported Greg Gibson, who ran the hardware strategy and reported to Todd Holmdahl, a senior executive who was an Xbox veteran. Mitch Koch ran sales and marketing and Bryan Lee led business strategy and planning. Laura Fryer took over Blackley’s Advanced Technology Group, which cooked up cool things to share with developers. Within that group, experts like Chris Prince figured out how to get a game machine to render things such as hair or fur.

Jonathan Hayes was tapped for industrial design. Don Coyner gathered marketing intelligence to help figure out the look and feel of the next machine, and he hired outside designers in a bake-off to help define what the next box and its components would look like.

Jonathan Hayes was tapped for industrial design. Don Coyner gathered marketing intelligence to help figure out the look and feel of the next machine, and he hired outside designers in a bake-off to help define what the next box and its components would look like.

The roles were far more defined compared to the original Xbox. It was a lot more corporate, which brought both added bureaucracy and more firepower.

“Where Xbox felt like we were doing a startup, Xbox 360 felt like we got our Microsoft mojo going,” Drew Angeloff, a member of the tools group, said recently. “We built up our staff and we could specialize. We no longer had to do 100 different jobs per person. I started to focus almost entirely on our external relationships with hardware vendors and tools and middleware providers.”

Newcomers like marketer David Reid arrived to help run the growing business. Larry Hyrb came aboard to help program Xbox Live and eventually became the public face of Microsoft as podcaster Major Nelson. Allard had said that the first Xbox was “ready, fire, aim.” This time, everything was more deliberate, and by the end of it, 25,000 people would have a hand in the creation of the Xbox 360.

When Peter Moore (pictured right), former president of Sega of America, arrived as a top Xbox executive, he sat in a meeting with CEO Steve Ballmer, who went into one of his classic shouting routines. Noting that Xbox Live was Microsoft’s ace, he shouted, “Xbox Live!” and pounded the table. He did it over and over. “Xbox Live! Xbox Live! Xbox Live!” Then he slammed into the Polycom conference phone with his fist, breaking it. He looked sheepish. Ed Fries turned to the astonished Moore and said, “Welcome to Microsoft.”