3-30-300

Finally, in February 2003, the executive team gathered for a retreat at the Salish Lodge & Spa, overlooking the beautiful Snoqualmie Falls (pictured) that was the opening scene for the Twin Peaks television show. There, Bach came up with his 3-30-300 plan. Bach would set strategy with a 3-page memo; Allard would follow up with a 30-page execution plan; the rest of the team would fill in the details with a 300-page plan.

Bach wanted the Xbox division to be profitable in 2007. He wanted Xenon to launch in 2005, timed with the other console launches. That made sense because of the timing of the high-definition TV adoption, which promised much better quality games. That meant the Xbox life cycle would only be four years, but that was good because Microsoft was losing so much money on the first box.

He wanted the hardware to be break-even and for Microsoft to own its intellectual property for the chips. He targeted about 40 percent of the market, up from about 20 percent in the first generation. Xbox Live would be built into the next system. Bach came back from the retreat with a plan in place and he sent it to Gates and Ballmer on April 2, 2003. They approved it. Since they had been meeting with the executives every six weeks, they were plugged into the thinking.

For those who played Age of Empires, as Bach did, it was a classic “early rush” strategy, or catching your opponents off guard before they were ready. Later in the year, consultants figured out how to save Microsoft $300 million a year in its operations in the game business. But the company was still losing a billion dollars a year.

Defining Xenon

Defining Xenon

The Xe 30 team made the rounds with the game developers, collecting feedback. They focused on high-definition, a feature of game graphics dubbed procedural geometry, and building Xbox Live into the box. But the executives kept pushing back because Xenon was so uninspiring.

Because Microsoft had plenty of time to commission its own hardware, industrial design, and chips, it was able to contain the costs of the Xbox 360. That made it possible to make money on each console sold, thanks in part to the fact that Microsoft was willing to consider selling its machine at a higher $399 price. And that made it much easier to make a profit on the overall business.

The planning team now had to pull together an execution plan within about six months. Microsoft was taking longer than it wanted to sign the final contracts with IBM and ATI. The chip deals for the first Xbox locked in wasted performance and wasted costs. This time, that wasn’t going to happen.

Barry Spector, a Microsoft business development director who worked for finance chief Bryan Lee, had the job of being an emissary. In the spring of 2003, he started working with vendors on the short list. He knew he had to get the terms right, or it could turn out to be a financial catastrophe for Microsoft. Billions of dollars were at stake. He wanted checks against price gouging and bonuses for hitting schedules.

With ATI, Spector drove the negotiators — such as ATI’s engineering vice president, Bob Feldstein — crazy. Spector would say, “I want to drive a BMW, but I can only afford to buy a Yugo. I really can’t afford to pay for a BMW.” This was coming from a guy at one of the world’s richest corporations. Spector even went back repeatedly to Nvidia to try to cut a deal with them, despite the bad blood. Whatever the deal, Microsoft wanted to make sure it got access to cool new pixel shader technology.

In the summer of 2003, Jeff Andrews was getting nervous that they would run out of time to get the chips done. Key to the deals was that one day, Microsoft would be able to significantly cut costs by fusing the graphics chip and the microprocessor — the two most expensive chips — into a single chip, just as Sony had done with the PS 2. While Sony could do that because it was one company, it was a hurdle for Microsoft because the rights would be split among several companies that didn’t want to surrender intellectual property. Greg Gibson, the hardware design chief, had to pursue multiple design scenarios, depending on which vendor signed the contract.

Gibson joined Spector in the negotiations to get over the impasse, while Rick Bergman joined Feldstein on the ATI side. Finally, ATI agreed to penalties if it missed its schedule, and it agreed to allow Microsoft to shop for a second source on the chip and to fuse it into a microprocessor at some point. They signed a deal on August 12, 2003, leaving ATI with just a little over two years to deliver its graphics chips.

The engineers were designing the hardware to be cost-effective, but there were big fights that bubbled up to the top. As the executive team fought over the hard drive, Nick Baker and his engineers decided to rely on “virtualization,” or allowing a game to be saved regardless of what kind of storage device was there: a hard drive or a flash memory card. Laura Fryer took heat from game developers, who still insisted on the hard drive. She lost that battle, as Microsoft came up with a Solomon-like solution, where it would have a low-end version without a hard drive, selling for a lower price, and a high-end model with a hard drive that sold for more.

Developers such as Tim Sweeney (pictured above) at Epic Games hated that solution, as it meant many developers would target the lowest-common denominator, or a box without a hard drive, for their games. But Sweeney won a battle; Microsoft relented on a plan to contain the amount of main memory (random access memory, or RAM) at 256 megabytes. Sweeney convinced Microsoft to increase that to 512 megabytes, even though that was a commitment of an additional $1 billion in costs over time.

Microsoft had another huge fight over whether to use a DVD drive in the box, or something that rose as a counter to Sony’s Blu-ray drive. The HD DVD alliance arose in its place, but Microsoft decided it was too late in coming. Eventually, the DVD drive won. If game developers really needed the extra disk space, they could include a second DVD disk with their games.

One of the key decisions the engineers made was to put the huge power supply into the power cable, taking it out of the box itself. That made the power cable look like a boa constrictor that had swallowed a bar of gold. But nobody cared about that because the power cable would be out of sight. And it allowed the designers to make the box itself much smaller than the original Xbox, which Peter Moore had joked “was so big it couldn’t fit through the doorway in most Japanese homes.”

The marketing plan

The marketing plan

J Allard was still stewing a bit about the Newsweek cover story that talked about all the things the “Amazing PlayStation 2” would do. For Xenon, he wanted the system to be on the cover of Time magazine. He asked the team to conceive of what a Time magazine cover story would say about the launch of the Xbox 360. That inspired the team to think about how to market the new box.

The first Xbox was a hardcore gamer’s dream. But the second one had to broaden the audience, making gaming more approachable, social and interactive. David Reid (pictured right), took the lead role on the design team to represent the marketing team, which had a project it called “North Star” to synchronize Xenon with the rest of Microsoft’s plans for home entertainment.

That work involved working with Jeff Henshaw to define the non-game functions that the Xbox 360 would do. They started with a wish list of 150 items and tried to narrow it down to 10 priorities. One of those ideas was to put a Media Center Extender into the Xbox 360, so that it could play content that was stored on a networked PC. That was one way the box could be more broadly appealing and reach the goal that Allard envisioned: reaching a billion people. And it was something that Sony couldn’t do.

At the same time, Microsoft had to avoid throwing the kitchen sink into the machine, a problem that was slowing Sony down. The team considered staging a global launch, debuting machines in Asia, Europe and North America at the same time. But they decided the marketing costs associated with such a launch were prohibitive.

One marketing idea raised a huge stink. Reid’s team had determined that so many Xbox fans were playing Halo 2 on multiplayer — long after the game shipped — that Microsoft had to enable that game to run on the Xbox 360 if it wanted to get those players to shift to the new game box. That brought back the technical challenge of backward compatibility. J Allard hated the idea, as it required him to take some of his very best software programmers and reassign them to do something which had been ruled out earlier as stupid.

Allard threw a huge fit. But he went to his team of ninja programmers and made it happen.Very late in the game, Microsoft went to IBM to ask it to support emulation, which would allow backward compatibility so that older Xbox games like Halo 2 would run on the Xbox 360. IBM had to make some modifications to enable the emulation.

Meanwhile, a branding team figured out what to call Xenon. Clearly, Microsoft couldn’t call it the Xbox 2, because that would sound inferior to the expected PlayStation 3. Don Hall, a branding manager, ran with the idea of putting the gamer at the center of a 360 degree circle. Xbox 360 was the name that stuck.

Industrial design

Industrial design

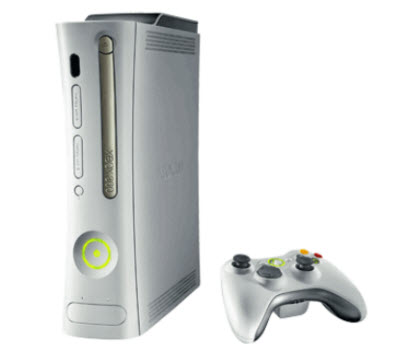

The first Xbox taught Microsoft the importance of industrial design, largely because it generated so many complaints. So the approach to the new console was much more methodical.

Don Coyner, a former Nintendo marketer, was appointed the “director of user experience” for the new machine. He had to collect intelligence, organize design bake-offs, and manage the people who came up with the industrial design.

The older system was roundly criticized as the result of a mad rush. It was big and intimidating. This machine had to fit in with the rest of the things people had in front of their beautiful flat-screen TVs. And it had to have “sofa,” or “significant other factor of acceptance.”

In February 2003, Coyner traveled the globe and collected design “gestures,” or early submissions for prototypes, from six design firms. To run the internal industrial design, Coyner turned to Jonathan Hayes, a non-gamer who had been designing joysticks and early smart phones.

In February 2003, Coyner traveled the globe and collected design “gestures,” or early submissions for prototypes, from six design firms. To run the internal industrial design, Coyner turned to Jonathan Hayes, a non-gamer who had been designing joysticks and early smart phones.

Nothing was working great, so Hayes invited a pitch from Astro Studios in San Francisco. They came up with the design that eventually became the winning one and worked with Japan’s design house, Hers Experimental Design Laboratory, to implement it. While the original Xbox looked like it was about to explode, the Xbox 360 looked like it was inhaling.

One of their signature ideas was “the ring of light,” which was the on/off button for Xbox 360. It had four glowing green lights, each of them divided into quadrants around a the ring that told the gamer which wireless controllers were operational. Later on, the rings would come to mean something else.

But for once, something that Microsoft designed looked cool. It even looked like Apple could have designed it. It would look nice in the stack of other consumer electronics boxes in the living room.

By the fall of 2003, Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer reviewed everything. And they gave it the green light. The big green Xbox was more like The Incredible Hulk. This time, the machine would be more like Bruce Lee. The final box would have more than 1,700 components in it, but it would look beautiful on the outside.

On the business side, Steve Ballmer and Bill Gates looked at the plan. Gates was still clinging to the idea of getting Windows to run on the Xbox, and raised the option of creating a high-end Xbox that could be a full Media Center PC. A team was assigned to explore the idea, code-named Helium, but the team never pulled it together.

Bach had reiterated his decision that Microsoft wasn’t going to lose money on hardware, period. But he wasn’t being cheap. Microsoft’s leaders were willing to commit Microsoft on a path that meant spending $17 billion on the game business over the course of a decade. The whole team was now free to execute on a plan.