The Xbox 360’s comeback with Kinect

To this day, the Wii holds the largest market share. Nintendo has sold 89.5 million Wii consoles, for a 44 percent market share. Microsoft has sold about 57.9 million Xbox 360s, for a 28.6 percent share. And Sony has sold 55.4 million PlayStation 3s, for a share of 27.3 percent. Meanwhile, Nintendo has sold 149.3 million DS portables, and Sony has sold 70.9 million PlayStation portables.

That’s usually where the calculations end. But it’s worth pointing out that Apple has sold more than 250 million iOS devices, and every one of them can play games. Zynga has more than 205 million monthly active gamers. Those are numbers that Microsoft clearly wishes it had for Xbox Live, which never really flourished as the marketplace for indie games in the way that would have made both the iPhone and Facebook irrelevant. It was a lost opportunity.

The story of the Xbox might have ended there, but Microsoft pulled a rabbit out of its hat. For the last 12 months, the Xbox 360 has been the fastest-selling console in the U.S. Nintendo’s Wii sales have fallen off a cliff, and Sony hasn’t been able to beat Microsoft in spite of shipping the PlayStation Move controller. Last month, Microsoft had 44 percent of the console market.

The reason is Kinect, the motion-sensing system for the Xbox 360 that shipped in the fall of 2010. Kinect, began as Project Natal (named after a city in Brazil) in Microsoft Research as long as a decade ago. There, it started as research on natural user interfaces, or ways to communicate with a computer beyond the mouse and keyboard, said Shane Kim, former head of Microsoft Game Studios. After the Wii came out, it became a higher priority at Microsoft. The engineering project came together within 18 months.

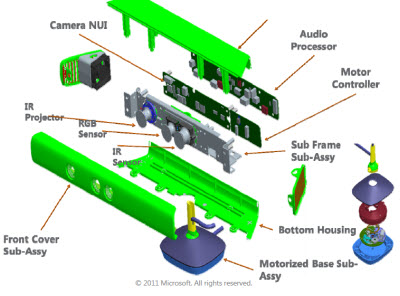

While the Wii and Sony’s PlayStation Move controller track single points on a handheld controller, Kinect detects your whole body’s movement using 3D depth cameras, which send signals into the entire room that bounce back and give the image sensor a 3D map of the room in real-time. Kinect also has three microphones for capturing your voice and recognizing commands. It sends the data into the Xbox 360, which can interpret the signals as commands for games. No game controller is necessary.

While the Wii and Sony’s PlayStation Move controller track single points on a handheld controller, Kinect detects your whole body’s movement using 3D depth cameras, which send signals into the entire room that bounce back and give the image sensor a 3D map of the room in real-time. Kinect also has three microphones for capturing your voice and recognizing commands. It sends the data into the Xbox 360, which can interpret the signals as commands for games. No game controller is necessary.

Kinect was viewed as the Wii on steroids. Microsoft locked up the technology by purchasing 3DV Systems, a motion-sensing chip maker. It also used a motion-sensing chip from PrimeSense. It licensed technology from GestureTek, and after Kinect shipped it finally bought 3D depth chip maker Canesta. Despite all those purchases, Kim felt the secret sauce was in software.

“To me, the magic is more software,” he said. “You’re talking about an extraordinary amount of data that has to be processed in real-time. You saw the latency was very good yesterday. You can parse voices, recognize faces. It’s complex hardware, even more sophisticated software, and simplified for developers to use it immediately. All of that so that consumers can have the most simplistic and easy experience to get into gaming.”

Microsoft also learned its lesson with hardware. Engineers Dawson Yee and Scott McEldowney said at a conference this summer that their team engineered Kinect to be as sturdy as possible. It was design to withstand high temperatures, drops, careless shipping, abusive gamers, a sudden loss of power and even surges from lightning strikes.

“You had to test it by dropping it on concrete,” said Yee, who has worked at Microsoft for 12 years and at Intel for a decade before that. “That was the level of robustness.”

One of the tough things was that Microsoft’s hardware engineers had to design the system out of thin air. They didn’t know exactly how software creators would use it. Nintendo had made the motion-sensing Wii, which depends on hand-held Wiimotes. But Microsoft had to design something with different kinds of sensors that were capable of sending signals around a room and then receiving them so that it could produce a digital representation of the spatial features of that room, without depending on remote controllers. The system had to see what was in the room, who was moving, and what they were doing. While the Wii could detect your arm motion, Kinect could go further. If you want to kick a ball in a Kinect game, you make a motion with your leg to kick a ball.

One of the tough things was that Microsoft’s hardware engineers had to design the system out of thin air. They didn’t know exactly how software creators would use it. Nintendo had made the motion-sensing Wii, which depends on hand-held Wiimotes. But Microsoft had to design something with different kinds of sensors that were capable of sending signals around a room and then receiving them so that it could produce a digital representation of the spatial features of that room, without depending on remote controllers. The system had to see what was in the room, who was moving, and what they were doing. While the Wii could detect your arm motion, Kinect could go further. If you want to kick a ball in a Kinect game, you make a motion with your leg to kick a ball.

On the outside, Microsoft watchers noticed yet again that Microsoft was shutting down a lot of its longtime projects such as the Flight Simulator studio. At the time, it seemed like the company was in a retreat from the game business. But a lot of those developers were reassigned to a higher priority: making games for the Kinect launch that would take full advantage of the system and appeal to a wider audience.

Raising its ambitions once again, Microsoft, under the leadership of former Electronic Arts executive Don Mattrick, aimed Kinect at the mass market. It commissioned games like Kinect Sports or Kinect Adventures to capture the same kind of non-gamers that Nintendo snared with the Wii: the people who would never pick up a game controller. It added the ability to control your TV or movie viewing with voice commands for fast forwarding or playback. Like Nintendo’s Wii ads, Microsoft’s ads for Kinect focused on the fun that players were having.

Kinect represented Microsoft’s return to innovation and thought leadership. The result was that Kinect became the fastest-selling accessory in the history of the game industry. Microsoft also claimed it was the fastest-selling consumer electronics device in all of history. In its first season, it sold more than 8 million units. Indeed, Microsoft had the honor of having the worst snafu in consumer electronics history, and its biggest success.

Kinect is something that neither Sony nor Nintendo — even with its revolutionary Wii motion-sensing technology — has duplicated. Microsoft introduced Kinect a year ago, and it has outsold Sony’s PlayStation Move motion-sensing controller by far. It was the kind of innovation that some observers thought should have accompanied the launch of the Xbox 360 in 2005.

“This is an example of where Microsoft shines and Sony and Nintendo should be worried,” said Rob Wyatt, the former Xbox architect.

Added Ed Fries, former head of Microsoft’s game studios, “Kinect showed that Microsoft could expand its audience and continue to innovate on the platform even later in its life cycle.”

The impact of the Xbox

The impact of the Xbox

Ten years after Microsoft shipped the first Xbox, the console wars continue. Nintendo is gearing up to ship the Wii U next year. Microsoft and Sony are reported to be working on their next game consoles. The war isn’t over. But Microsoft has made enough progress to be able to make some bold claims.

“The Xbox 360 was the accelerant that took us from membership to leadership,” Robbie Bach, the former chief Xbox officer, said recently.

Some of the impact of the Xbox seems mundane for consumers, but easing the development pains became critical for game developers, particularly as costs spiraled toward $30 million per game.

“I think the significance is that with Microsoft’s entrance into the console space, the console space was infused with new ideas about what developer platforms should look like (Xbox Developer Kit, Visual Studio) what support should be like (Xbox ATG), what connected entertainment is (Xbox Live), and the exploration of new ideas and paradigms in gaming that can broaden gaming demographics (like Kinect),” said Drew Angeloff.

Chris Prince, the former Advanced Technology Group member, said, “One of the long-lasting effects of Xbox is an emphasis on ease of development. Or, to perhaps put it differently, the idea that software is king, not hardware.”

For consumers, the Xbox has generated billions of hours of entertainment. Those who experience that fun may call it mindless, or they may call it experiencing a new art form. It was part of a broader movement that made the process of making games into one of the coolest professions. Before, if you introduced yourself as a game designer at a party, people saw you as a geek, Blackley said. Now, it is one of the coolest jobs available.

“Xbox really opened my eyes,” Blackley said. “It showed me what stood in the way of creative people. The most important people in the business are gamer designers. Everything you do in their favor is good. Everything you do against them is suicide.”

The newfound respect for game developers means that more people are viewing games as acceptable and respectable. Microsoft’s entry into games was a brand endorsement that made it OK to be gamers. And it enabled game developers to legitimately claim that they were making works of art.

A.J. Redmer said, “I think Microsoft would consider it to be the company’s biggest success over the past decade. It has taken the lead over Windows when driving the user experience in areas like mobile devices, smartphones, music players and other things.” Redmer said that the system and services targeted what the team called DEL, or the Digital Entertainment Lifestyle. In fact, it became a hub for watching TV, streaming music and movies, photo and video sharing and other non-game content.

Xbox also put games on the road to becoming the biggest form of entertainment. Thanks in large part to sales on the Xbox 360, Activision Blizzard has been able to claim for the last three years running that its Call of Duty game launches have been the fastest-selling entertainment launches in history for any medium. Last week, Call of Duty Modern Warfare 3 sold more than 6.5 million units and generated $400 million in revenues in a single day. Most of those who played that game online played it on Xbox Live.

The Xbox diaspora

The Xbox diaspora

The Xbox did another good thing for the industry. It pulled a team together, honed them in a very intense experience, and spun them out again into the industry. Some liked it so much they stuck around for the Xbox 360. But many left. Alex St. John was out the door before Xbox really began. He is now the president of game-focused social network Hi5.

Peter Moore, who ran the Xbox team under Bach, left to join Electronic Arts to head its sports game label and is now chief operating officer there.

Steve Perlman, who had sold WebTV to Microsoft for $425 million, took his money and started an incubator called Rearden. He founded companies such as Moxi Digital, Mova, and helped Andy Rubin, former head of Danger, maker of the Sidekick phone, start something called Android. Google bought it and turned it into a mobile operating system phenomenon. But Perlman’s focus has been on OnLive, a game streaming venture that, if it works, will make game consoles obsolete.

Kevin Bachus, Blackley’s sidekick, also left before the Xbox launched. He wound up at Capital Entertainment Group with Seamus Blackley, who had stayed at Microsoft through early 2002. He stayed through the launch and resigned on the day that my book, Opening the Xbox, was published in the spring of 2002. At CEG, Bachus and Blackley tried to create a financing and production machine for game developers, but they were starved for capital themselves and never got off the ground.

Bachus went on to other game companies and wound up as the No. 2 executive at Bebo. Blackley spent years at Creative Artists Agency representing game designers and getting them their fair share of royalties and ownership of their intellectual property. He left this summer to work on a new startup in games.

Ted Hase, one of the four co-founders of the Xbox, left Microsoft in 2004. He is now vice president of research and development and global games at Aristocrat Technologies. Otto Berkes, another co-founder, worked at Microsoft on low-power handheld technologies through mid-2011. He recently left to join an unnamed startup.

Cameron Ferroni left Microsoft, but his buddy J Allard stayed through the Xbox 360, the Zune, and the design of a tablet called Courier. After that was canceled, Allard left in 2010. Allard hasn’t surfaced yet, but Ferroni is vice president of engineering and operations for TheClymb, an online flash sales site for outdoor gear.

Robbie Bach also left the company in 2010, retiring after a glorious business career of 22 years at Microsoft. Allard and Bach had a long run, presiding over Microsoft’s greatest successes and some of its worst failures.

Rob Wyatt went on to work on the PlayStation 3 for Sony and worked on games at Insomniac Games. He recently became chief scientist at game streaming firm Otoy and is writing game reviews for VentureBeat.

Since retiring from Microsoft in 2004 after more than two decades there, Ed Fries continued to work in the video game business as a board member, advisor, consultant and speaker for many game companies around the world. He’s part owner of a game company and runs his own high-tech startup. Shane Kim, Fries successor, also retired from Microsoft and is now advising startups.

A.J. Redmer, who helped put the Xenon plan together, left Microsoft in 2006 after seven years on the Xbox team. He now serves on the boards of international companies and is based in Austin, Texas.

Chris Prince, the former member of the Advanced Technology Group and one of the hardware designers, left in 2004 to work at Google, where he stayed for seven years as technical lead for Google Voice. He is now at a startup. Mike Sartain of the ATG left in November, 2001 and spent 10 years with Abrash at Rad Game Tools. He joined Valve Software earlier this year to work on Defense of the Ancients 2.

Horace Luke went on to do a number of internal projects but left to lead smartphone design for HTC. He recently left that job for something new.

Drew Angeloff left Microsoft after the Xbox 360 to work at ATI Technologies, which was later acquired by Advanced Micro Devices. After that, he returned to work on Microsoft’s XNA game development program and Windows Phone. Now he is in charge of production at Turn 10 Studios, which just shipped the Forza Motorsport 4 game.

David Hufford has played a variety of roles since the launch, but is back in charge leading the public relations team. Oddly enough, Hufford didn’t organize any public recognition of the 10th anniversary of the Xbox launch. Microsoft has recreated a version of its blockbuster Halo game (now called Halo CE Anniversary) to celebrate its 10th anniversary. But that’s it.

Occasionally, the team has reunions at different events. Of those interviewed recently for the story, all of them said the most memorable things about the Xbox were the people on the team. We regret we couldn’t reach everyone. Not everybody got proper recognition for their work.

“The Greeks said nostalgia is a disease,” Blackley said. “It interferes with your ability to live in the day. If you worry about getting credit about something, it should remind you that you are not doing something yourself at the moment that is fulfilling. But we all know that, in that first year, if someone failed to do their job, it was the life or death of the project. In the end, it’s so awesome. I’m really proud of those of us who stuck our necks out to get it going.”

Related articles

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More