Leaving and coming back

Above: Fox News interviews John Riccitiello. (Courtesy of Fox)

At the time of the bubble’s collapse, EA didn’t fire Riccitiello, but he eventually left on his own. In 2004, Silicon Valley was still amid its “nuclear winter,” the post-dotcom crash era when investment had dried up. But after leaving EA that spring, Riccitiello hooked up with investor Roger McNamee and U2 lead singer Bono to create Elevation Partners.

They assembled a big fund and decided to pour their money into entertainment startups, including game development companies, which had always been undervalued even after they were proven hit machines. Riccitiello put $400 million into Josh Resnick’s Pandemic Studios and BioWare, the successful studio of Ray Muzyka and Greg Zeschuk, two former doctors who had built addictive role-playing games.

Meanwhile at EA, Erin Hoffman, writing under the pseudonym EA Spouse, blew the lid on the harsh, family-unfriendly culture that required employees to work all the time. The result was multiple class-action lawsuits, and EA had to pay millions to workers for unpaid overtime. EA’s “crunch time” all the time became a symbol of all that was wrong with the game industry. It was thriving as a profitable business, but under the hood, things were dirty.

During the time that Riccitiello left, the company did OK from 2004 to 2007.

In 2005, EA bought Jamdat Mobile, the largest player in mobile games. That meant EA was investing heavily in mobile before Apple created the iPhone. That kind of learning gave it a big advantage as the era of apps took off. To further get its mojo back, Probst made a bold play. He agreed to acquire BioWare-Pandemic for $800 million. And Riccitiello became CEO while Probst stayed on as chairman. Almost in reaction, Activision and Blizzard Entertainment merged to become EA’s biggest rival.

But Riccitiello made no secret about the problems that he observed at EA when he returned. As he saw it, by 2008, EA had seen its development costs skyrocket with the transition to the high-def consoles, the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3. Its product quality had suffered, and it had missed seeing the mass appeal of the Nintendo Wii, which debuted in 2006 and became a spectacular hit. Gamers no longer enjoyed licensed titles based on movies. By the time EA moved to that platform, the Wii had begun to cool off. Riccitiello launched his own hostile bid to acquire Take-Two Interactive, the maker of Grand Theft Auto and Red Dead Redemption, but that attempt failed.

“Our profits were in rapid decline before they went entirely negative,” Riccitiello recalled in his 2011 speech. He said he told employees that the company had to go through a radical change or accept a “shrinking share of a shrinking pie and eventually die.” EA had to adapt to the digital gaming world, which included everything from smartphones to Facebook games to downloadable content on consoles. It also had to dramatically improve quality and push beyond retail games into online distribution. And for the first time, EA had to dramatically cut headcount.

In 2009, the world fell apart with the global financial crisis. EA’s stock took a tumble from the highs of 2007 and never recovered. Zynga grew rapidly with titles like FarmVille, opening a whole new market for games on Facebook. To catch up, EA paid as much as $400 million to acquire social gaming firm Playfish. EA laid off 1,500 employees in October 2009 on the same day it announced that deal. Many viewed the acquisition of Playfish as an admission of failure — that EA couldn’t beat rivals such as Zynga on its own. But it was a savvy way to catch up as well.

“We knew it would be hard, but we had no idea how hard,” he said in his 2011 speech. “We had to do these three hard things when the press and the financial analysts told us we were crazy — that the cutting was great, but the investment in digital was just not a good idea. It proved very hard to hear the negative drumbeat while tackling very hard challenges at work.”

In the meantime, Activision and Blizzard Entertainment executed well on their merger. Blizzard’s World of Warcraft held off challengers to its supremacy in online games. Activision’s Call of Duty series became a huge juggernaut for military shooters and online multiplayer. EA fought valiantly with the relaunch of the Battlefield series, particularly with the successful launch of Battlefield 3. But its Medal of Honor reboot failed, and Activision remains dominant in the multibillion-dollar shooter market.

Other rivals, like Zynga, DeNA, Gree, Take-Two Interactive, Valve, Wargaming.net, and Riot Games, succeeded (at least for a time in some cases) in spectacular fashion in their own corners of the business. The success of those companies made EA’s own victories seem meager by comparison.

In 2011, EA fought back in a big way, acquiring casual game publisher PopCap Games for at least $750 million. That deal tied up a lot of EA’s cash hoard, but it has had unclear results.

Riccitiello takes it personally

Anybody who knew Riccitiello during this time understood how much value he placed on loyalty. During EA’s period of retrenchment, rivals left. It was galling to see John Pleasants (now head of Disney’s game division) leave and join rival Playdom. A day after he departed, EA’s PR folks made it clear that it told Pleasants he was being replaced first.

John Schappert, a former EA veteran and top Microsoft games executive, filled in for Pleasants. Then in June 2011, Zynga hired away Schappert to be the No. 2 to its CEO, Mark Pincus. Zynga was already rich with former EA executives, and its most influential board member was Bing Gordon, the former chief creative officer at EA and someone that Riccitiello knew well. They were all friendly competitors, but they were also fierce rivals.

Back in 2011, Riccitiello said, “I lost a few friends in the process: smart, creative people who just couldn’t stomach the transition.”

Many headed to other game companies for a quicker profit and payout.

Riccitiello said he was surprised and heartened at how many stayed purely on faith. He said EA could have scaled back on its ambitious plan to satisfy analysts or the press, but it did not. He promoted executives such as Muzyka, who executed well in taking the Mass Effect series from an Xbox exclusive to a multiplatform juggernaut. Riccitiello brought aboard Peter Moore, another former Microsoft games executive, as the head of EA Sports. He eventually promoted Moore to become chief operating officer. (Muzyka retired last year, along with his fellow BioWare cofounder Zeschuk.)

At one point, Riccitiello tried to poach some of Activision Blizzard’s best developers. Through then-Hollywood agent Seamus Blackley, he came into contact with Vince Zampella and Jason West, the co-founders of Infinity Ward, which made Call of Duty into Activision’s blockbuster. Activision discovered the communication, fired the two executives, and filed a lawsuit. Riccitiello eventually won Zampella and West over to EA’s fold, signing a deal with their new studio, Respawn Entertainment. The litigation spurred more bad blood between Riccitiello and Activision Blizzard CEO Kotick, but it was eventually settled.

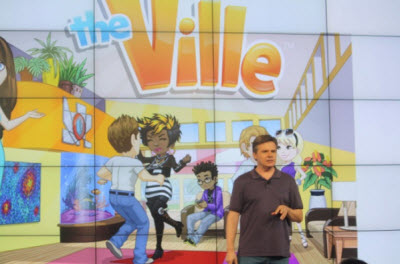

The downside of angering Riccitiello became evident in another lawsuit. After Zynga launched The Ville (with former EA manager Mark Skaggs, pictured above, leading the project), EA cried foul, alleging that it was a blatant rip off of its own The Sims Social, and sued for copyright infringement.

Zynga fired back in a counter-claim that Riccitiello was furious at it for hiring former EA executives. The company alleged that Riccitiello personally proposed an anti-competitive “no hire” pact with Schappert (who has since left Zynga), or he would “rain hell.” Zynga said that it had received more than 3,000 unsolicited resumes from EA employees. Riccitiello was reportedly so upset at Schappert’s hiring of executives such as Jeff Karp (former marketer of The Sims at EA) and Barry Cottle (former head of EA Mobile) that he got the legal team to file suit. In the filing, Zynga said that Riccitiello wrote to Schappert, “Some of our people will always leave. But they are leaving for one place — Zynga. … I get that they can reach out. The question is what happens when they do. Listen and send them back to me or their boss at EA. Or, listen, nod, and lend a hand. … We are crossing into a place I don’t think we want to be. … But I believe you can and should find more talent outside of EA.”

Zynga further said, “EA explicitly communicated to [us] that, although Zynga’s past hiring was lawful, EA’s chief executive officer John Riccitiello was ‘on the war path,’ ‘incensed,’ and ‘heated,’ and intent on stopping Zynga’s future hiring of EA employees.” When Cottle left EA in January 2012, Riccitiello reportedly said, “If Mr. Cottle reported back to work at EA, he would ‘pretend none of this ever happened,’ but if not, he would ‘rain hell’ on Mr. Cottle for the next several weeks.”

At the time, EA countered by saying, “This is a predictable subterfuge aimed at diverting attention from Zynga’s persistent plagiarism of other artists and studios. Zynga would be better served trying to hold on to the shrinking number of employees they’ve got rather than suing to acquire more.”

The two companies eventually settled the lawsuit. As Zynga’s own value crashed in the stock market, Riccitiello’s public stance toward rivals softened. But clearly, hardball was common among Riccitiello and the small circle of executives who worked with him or opposed him.

All of those examples of taking things personally showed just how tough Riccitiello could be. But regardless of what you think of those incidents, he was clearly always a fierce competitor when it came to acting in the interests of EA.