John Riccitiello left Electronic Arts yesterday with a mixed record.

In the nearly six years he led EA, the gigantic video game publisher faced a massive shift in the market, from games primarily sold on physical media and played on consoles to games sold and delivered wirelessly and played on everything from consoles to smartphones and tablets. The market shifted from expensive games you buy and own to free-to-play games that cost nothing to play at first, but which charge you for extras. The market expanded from the living room to mobile devices. Through it all, EA survived — which is more than some of its rivals can say — but it hasn’t exactly thrived.

In this story, we’ll try to recapture the ups and downs of Riccitiello’s tenure at the top of one of the video game industry’s most visible companies, and by the end of it, we’ll sort through the complex picture of his record at EA. We’ll also take a look at where the company is going in the future.

Lessons from success — and failure

Ostensibly, the board fired Riccitiello because he missed his quarterly and annual financial targets. In the past, the board might have excused this, since many companies were in the same boat. But at a time of great change in the video game business, so-so performance is no longer good enough. (EA’s temporary CEO is former chief executive Larry Probst, who is looking for a permanent replacement for Riccitiello.)

Still, it’s too simple to say that Riccitiello was a big screwup. In fact, Riccitiello was in many ways a very successful CEO who guided EA through a very difficult transition. By comparison, rivals such as THQ have crashed on the shoals of the digital gaming revolution while Riccitiello arguably saved EA from such a fate. But to demanding shareholders, merely surviving is not good enough. They want EA to seize the opportunities before it to become the dominant player in digital gaming. And it hasn’t quite done that.

EA declined to make an executive available for an interview for this story. But an EA spokesman said in a statement to GamesBeat, ” In the course of seven years, there’s a lot of puts and takes in that equation – recession, extended console cycle, etc. Beyond the macros, we knew this would be a difficult transition – one that required a great deal of investment in people and infrastructure. We knew that the ROI wasn’t going to be immediate. That said, it’s been more difficult than expected – the turnaround took longer than expected.”

Meanwhile, EA’s chief operating officer, Peter Moore, said on his Facebook page, “[Game news site] Kotaku reveling in what, due to their self-smugness, they don’t realize is a sad day for our industry, which is the platform on which they actually make money. John not only helped propel our company and interactive entertainment into new experiences, thus enticing millions of new people to become ‘gamers,’ his work leading the [Entertainment Software Association] in recent years has helped ensure that we don’t experience the fate of the music industry. Sad loss for all of us who had the pleasure of working with him as we emerged from The Burning Platform.”

Many rivals have beaten EA in small pieces of the larger industry war. If you can fault the company for anything, it may be for trying to fight too many battles at once.

The publisher didn’t lose all of those battles. In his parting message to his employees, Riccitiello pointed to their successes.

“Personally, I think we’ve never been in a better position as a company,” Riccitiello said. “You have made enormous progress in improving product quality. You are now generating more revenue on fewer titles by making EA’s games better and bigger. You’ve navigated a rapidly transforming industry to create a digital business that is now approximately $1.5 billion and growing fast.”

Above: John Riccitiello’s commencement speech in 2011. (Courtesy of UC Berkeley)

Riccitiello set many things in motion. But giving him credit or assigning blame is a complicated matter, as the execution always lies in the hands of thousands of employees.

It is easy to point to EA’s failures, such as Star Wars: The Old Republic, a massively multiplayer online role-playing game that took so long to finish that the market changed from underneath it, moving from lucrative subscriptions to free-to-play. After six years and perhaps $200 million in development costs, The Old Republic didn’t get the audience that EA had hoped for, and it had to shift to free-to-play to hang on to its players.

The reboot of the first-person military shooter Medal of Honor was a sad failure. More recently, big franchises like Crysis 3 and Dead Space 3 didn’t perform as expected. And the recent SimCity launch — which sold more units faster than any other title in the city-simulation game’s 24-year history — was marred by EA’s failure to provide enough servers for the always-connected game.

On the positive side, EA’s Battlefield military shooter series became a big hit, and FIFA Soccer has become a monstrous franchise, with a large component of digital revenues.

EA’s shares are down 60 percent since Riccitiello began. Shareholders and boards often show no mercy when they fire a CEO, and in this case, they had plenty of failures to point to as reasons to fire Riccitiello, who once told VentureBeat, “I don’t think investors give a shit about our quality.”

“Transitions are painful,” said P.J. McNealy, a longtime game industry follower and analyst at Digital World Research. “Look at Sony and the changes they had in leadership. EA has struggled. THQ has struggled. At some point, there has to be accountability for it. Typically, it’s not any one reason. But EA’s struggles are not limited to just this quarter.”

But it’s easy at a time like this to forget about Riccitiello’s successes and how each failure was also rich with learning.

“I’ve had first-hand experience with failure, and I have had the opportunity to learn and recover from it,” Riccitiello said in a speech at his alma mater, the Haas School of Business at the University of California at Berkeley, in 2011.

He’ll have plenty of time to ponder the lessons he learned at EA now.

In its own statement defending Riccitiello’s record, EA said to GamesBeat, “Our definition of turnaround swung on how quickly we could transition from the packaged goods model to digital goods and services. John made it clear that this was life or death. The dissolution of THQ this year makes it clear how right he was. By every measure, the turnaround is happening. As noted in an earnings call, this is the last year that digital revenue will be under 50 percent of EA’s total. One example is the first two weeks of [digital] sales for SimCity were just under 45 percent, and we expect the percentage will go even higher. Riccitiello’s turnaround is an article of faith inside EA – if it hadn’t happened, we wouldn’t be in business today.”

Riccitiello’s first tour of duty at EA

Riccitiello joined EA as chief executive in 2007. It was his second stint at the company. He had previously served as president and chief operating officer from 1997 through April 2004. He left in between to become a co-founder of Elevation Partners, a private equity investment firm that hatched the merger of game developers BioWare and Pandemic.

In his first tenure, Riccitiello was new to games. He had spent a career in consumer products at companies such as Clorox, Pepsi, Haagen-Dazs, Wilson Sporting Goods, and Sara Lee. Probst hired Riccitiello on the bet that his experience in consumer marketing would pay off at a time when video games were becoming a worldwide mass market. With properties like Madden NFL and FIFA Soccer, EA had become a household name. Its biggest rival today, Activision Blizzard, hadn’t yet been formed.

During Probst’s 16-year tenure as CEO, the company became the undisputed giant of the video game business. EA was the king maker, breaking Sega’s Dreamcast console when it chose not to create games for that platform and making the PlayStation 2 by throwing all of its weight behind Sony’s system. By the time Riccitiello joined, EA was in its glory years, and it was looking at how to further exploit its position as a giant in sports games, licensed movie titles, and online games.

He was a newcomer to games, but Riccitiello immersed himself in them as a player and as a cultivator of talent. Probst, the former chief executive and now the acting CEO again, and Activision Blizzard CEO Bobby Kotick have both admitted to not being gamers, or at least not the really hardcore kind. But Riccitiello played games and tried to understand the way they were built. He was sharp and a quick study and formed relationships with key creators.

Riccitiello made contributions, but always as part of a larger executive team. He and studio chief Don Mattrick encouraged the company to get behind Will Wright, who was working on a dollhouse-like title that would later become The Sims, the best-selling EA game series of all time. Riccitiello encouraged his leaders to take risks, egging Neil Young to create a visionary title in Majestic, an early alternate-reality game that turned into a commercial flop. In one case, Riccitiello made a brilliant bet. In the other, the outcome was a dud. These results would be typical of Riccitiello’s life at EA. He could share a vision with marquee developers and get behind them like a zealot. Sometimes it panned out; sometimes it didn’t. But he was always willing to bet big.

Riccitiello’s job was to diversify EA, and he did so through acquisitions of companies like Pogo.com, a casual game website for older, less serious players. EA picked up Westwood Studios, the creator of the Command & Conquer real-time strategy series; and Dreamworks Interactive, the original developer of Medal of Honor. It also bulked up with acquisitions of racing game studios and rode the success of titles based on the Harry Potter books and films. EA stole the James Bond 007 movie-game license from Nintendo, convincing the Hollywood owner that it could take the series multiplatform. Riccitiello and executive Frank Gibeau played a role in that coup. EA came to specialize in multiplatform blockbusters.

The company had become so dominant during the era of the PlayStation 2 that developers feared it would homogenize the industry and drive out all of its creativity. That led some to do everything they could to stay out of EA’s clutches, an issue that persists today. EA’s acquisitions follow a pattern. Some thrive for a while, but as soon as their magic wares off, EA shuts them down and puts its efforts behind another.

And during the run-up of the huge dotcom boom, Riccitiello searched for a way for EA to cash in. After Richard Garriott’s Ultima Online became the first major hit in massively multiplayer online games, Riccitiello started EA.com, a web games business that would be home to a whole collection of MMOs. With these games, EA could keep much more of the profit since it charged subscription fees. Under Riccitiello, EA initiated big-budget online titles like Motor City Online, Earth & Beyond, The Sims Online, and Ultima Online 2.

But the dotcom bubble burst and brought down everything with it. That was a costly lesson. EA wrote off more than $400 million. Of all of the things that Riccitiello had achieved at EA, the failure of EA.com would, fairly or not, become a huge part of his legacy. You could argue that he had been caught up in the Internet wave and that he deserved to be fired for making the wrong bet. But then, you could also fire just about everybody in Silicon Valley, where EA is based, for the same thing.

During Riccitiello’s stay as the No. 2 executive at EA, the company got bigger and stronger. It had setbacks, but that’s entertainment.

Leaving and coming back

Above: Fox News interviews John Riccitiello. (Courtesy of Fox)

At the time of the bubble’s collapse, EA didn’t fire Riccitiello, but he eventually left on his own. In 2004, Silicon Valley was still amid its “nuclear winter,” the post-dotcom crash era when investment had dried up. But after leaving EA that spring, Riccitiello hooked up with investor Roger McNamee and U2 lead singer Bono to create Elevation Partners.

They assembled a big fund and decided to pour their money into entertainment startups, including game development companies, which had always been undervalued even after they were proven hit machines. Riccitiello put $400 million into Josh Resnick’s Pandemic Studios and BioWare, the successful studio of Ray Muzyka and Greg Zeschuk, two former doctors who had built addictive role-playing games.

Meanwhile at EA, Erin Hoffman, writing under the pseudonym EA Spouse, blew the lid on the harsh, family-unfriendly culture that required employees to work all the time. The result was multiple class-action lawsuits, and EA had to pay millions to workers for unpaid overtime. EA’s “crunch time” all the time became a symbol of all that was wrong with the game industry. It was thriving as a profitable business, but under the hood, things were dirty.

During the time that Riccitiello left, the company did OK from 2004 to 2007.

In 2005, EA bought Jamdat Mobile, the largest player in mobile games. That meant EA was investing heavily in mobile before Apple created the iPhone. That kind of learning gave it a big advantage as the era of apps took off. To further get its mojo back, Probst made a bold play. He agreed to acquire BioWare-Pandemic for $800 million. And Riccitiello became CEO while Probst stayed on as chairman. Almost in reaction, Activision and Blizzard Entertainment merged to become EA’s biggest rival.

But Riccitiello made no secret about the problems that he observed at EA when he returned. As he saw it, by 2008, EA had seen its development costs skyrocket with the transition to the high-def consoles, the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3. Its product quality had suffered, and it had missed seeing the mass appeal of the Nintendo Wii, which debuted in 2006 and became a spectacular hit. Gamers no longer enjoyed licensed titles based on movies. By the time EA moved to that platform, the Wii had begun to cool off. Riccitiello launched his own hostile bid to acquire Take-Two Interactive, the maker of Grand Theft Auto and Red Dead Redemption, but that attempt failed.

“Our profits were in rapid decline before they went entirely negative,” Riccitiello recalled in his 2011 speech. He said he told employees that the company had to go through a radical change or accept a “shrinking share of a shrinking pie and eventually die.” EA had to adapt to the digital gaming world, which included everything from smartphones to Facebook games to downloadable content on consoles. It also had to dramatically improve quality and push beyond retail games into online distribution. And for the first time, EA had to dramatically cut headcount.

In 2009, the world fell apart with the global financial crisis. EA’s stock took a tumble from the highs of 2007 and never recovered. Zynga grew rapidly with titles like FarmVille, opening a whole new market for games on Facebook. To catch up, EA paid as much as $400 million to acquire social gaming firm Playfish. EA laid off 1,500 employees in October 2009 on the same day it announced that deal. Many viewed the acquisition of Playfish as an admission of failure — that EA couldn’t beat rivals such as Zynga on its own. But it was a savvy way to catch up as well.

“We knew it would be hard, but we had no idea how hard,” he said in his 2011 speech. “We had to do these three hard things when the press and the financial analysts told us we were crazy — that the cutting was great, but the investment in digital was just not a good idea. It proved very hard to hear the negative drumbeat while tackling very hard challenges at work.”

In the meantime, Activision and Blizzard Entertainment executed well on their merger. Blizzard’s World of Warcraft held off challengers to its supremacy in online games. Activision’s Call of Duty series became a huge juggernaut for military shooters and online multiplayer. EA fought valiantly with the relaunch of the Battlefield series, particularly with the successful launch of Battlefield 3. But its Medal of Honor reboot failed, and Activision remains dominant in the multibillion-dollar shooter market.

Other rivals, like Zynga, DeNA, Gree, Take-Two Interactive, Valve, Wargaming.net, and Riot Games, succeeded (at least for a time in some cases) in spectacular fashion in their own corners of the business. The success of those companies made EA’s own victories seem meager by comparison.

In 2011, EA fought back in a big way, acquiring casual game publisher PopCap Games for at least $750 million. That deal tied up a lot of EA’s cash hoard, but it has had unclear results.

Riccitiello takes it personally

Anybody who knew Riccitiello during this time understood how much value he placed on loyalty. During EA’s period of retrenchment, rivals left. It was galling to see John Pleasants (now head of Disney’s game division) leave and join rival Playdom. A day after he departed, EA’s PR folks made it clear that it told Pleasants he was being replaced first.

John Schappert, a former EA veteran and top Microsoft games executive, filled in for Pleasants. Then in June 2011, Zynga hired away Schappert to be the No. 2 to its CEO, Mark Pincus. Zynga was already rich with former EA executives, and its most influential board member was Bing Gordon, the former chief creative officer at EA and someone that Riccitiello knew well. They were all friendly competitors, but they were also fierce rivals.

Back in 2011, Riccitiello said, “I lost a few friends in the process: smart, creative people who just couldn’t stomach the transition.”

Many headed to other game companies for a quicker profit and payout.

Riccitiello said he was surprised and heartened at how many stayed purely on faith. He said EA could have scaled back on its ambitious plan to satisfy analysts or the press, but it did not. He promoted executives such as Muzyka, who executed well in taking the Mass Effect series from an Xbox exclusive to a multiplatform juggernaut. Riccitiello brought aboard Peter Moore, another former Microsoft games executive, as the head of EA Sports. He eventually promoted Moore to become chief operating officer. (Muzyka retired last year, along with his fellow BioWare cofounder Zeschuk.)

At one point, Riccitiello tried to poach some of Activision Blizzard’s best developers. Through then-Hollywood agent Seamus Blackley, he came into contact with Vince Zampella and Jason West, the co-founders of Infinity Ward, which made Call of Duty into Activision’s blockbuster. Activision discovered the communication, fired the two executives, and filed a lawsuit. Riccitiello eventually won Zampella and West over to EA’s fold, signing a deal with their new studio, Respawn Entertainment. The litigation spurred more bad blood between Riccitiello and Activision Blizzard CEO Kotick, but it was eventually settled.

The downside of angering Riccitiello became evident in another lawsuit. After Zynga launched The Ville (with former EA manager Mark Skaggs, pictured above, leading the project), EA cried foul, alleging that it was a blatant rip off of its own The Sims Social, and sued for copyright infringement.

Zynga fired back in a counter-claim that Riccitiello was furious at it for hiring former EA executives. The company alleged that Riccitiello personally proposed an anti-competitive “no hire” pact with Schappert (who has since left Zynga), or he would “rain hell.” Zynga said that it had received more than 3,000 unsolicited resumes from EA employees. Riccitiello was reportedly so upset at Schappert’s hiring of executives such as Jeff Karp (former marketer of The Sims at EA) and Barry Cottle (former head of EA Mobile) that he got the legal team to file suit. In the filing, Zynga said that Riccitiello wrote to Schappert, “Some of our people will always leave. But they are leaving for one place — Zynga. … I get that they can reach out. The question is what happens when they do. Listen and send them back to me or their boss at EA. Or, listen, nod, and lend a hand. … We are crossing into a place I don’t think we want to be. … But I believe you can and should find more talent outside of EA.”

Zynga further said, “EA explicitly communicated to [us] that, although Zynga’s past hiring was lawful, EA’s chief executive officer John Riccitiello was ‘on the war path,’ ‘incensed,’ and ‘heated,’ and intent on stopping Zynga’s future hiring of EA employees.” When Cottle left EA in January 2012, Riccitiello reportedly said, “If Mr. Cottle reported back to work at EA, he would ‘pretend none of this ever happened,’ but if not, he would ‘rain hell’ on Mr. Cottle for the next several weeks.”

At the time, EA countered by saying, “This is a predictable subterfuge aimed at diverting attention from Zynga’s persistent plagiarism of other artists and studios. Zynga would be better served trying to hold on to the shrinking number of employees they’ve got rather than suing to acquire more.”

The two companies eventually settled the lawsuit. As Zynga’s own value crashed in the stock market, Riccitiello’s public stance toward rivals softened. But clearly, hardball was common among Riccitiello and the small circle of executives who worked with him or opposed him.

All of those examples of taking things personally showed just how tough Riccitiello could be. But regardless of what you think of those incidents, he was clearly always a fierce competitor when it came to acting in the interests of EA.

Unlucky in the blue ocean

The series of above-mentioned personal incidents served as a reminder that Riccitiello could be trapped into seeing the world as a zero-sum game. Like his rivals, he would battle in the red ocean (where the sharks are fighting for the red meat) rather fight in the blue ocean (or parts of the market where no one is playing). If Activision had a hit with Guitar Hero, Riccitiello attacked it with Rock Band. He went after Call of Duty’s success by rebooting Battlefield and Medal of Honor. And after Zynga scored with CityVille, Riccitiello struck back with SimCity Social.

If any one of the titles struck gold, then EA would make sequel after sequel. That earned the ire of consumers and game developers who want more creativity in games, not homogeneity. Riccitiello engaged in copycat wars. Sometimes, he accused his rivals of copying him, and sometimes it was the other way around. It was a kind of trap, and it explained why some gamers became disillusioned with the state of the overall traditional video game market, which has been shrinking since 2010.

“Taking on Activision in head-to-head competition was not a good strategy,” said P.J. McNealy at Digital World Research.

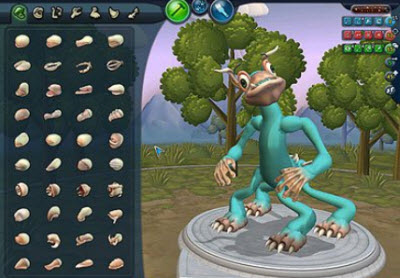

For sure, Riccitiello made some huge bets in blue ocean games that were risky. He backed Spore, the first major project that Will Wright undertook after making The Sims. The game received great ratings and sold millions of units. But it was nowhere near as big a hit as The Sims was. In that sense, it was a victim of unrealistic expectations. Riccitiello greenlit some major games such as the sci-fi horror series Dead Space.

Riccitiello was a big advocate of publishing third-party games through a program dubbed EA Partners. In doing so, EA stepped back into a role of a distributor, fulfilling demand for games from major third-parties. EA still has some big partner games in the works, like the one coming from Respawn Entertainment.

In more recent years, EA has retreated from offering many new intellectual properties to focusing on proven franchises such as Battlefield, Need for Speed, FIFA Soccer, Madden NFL Football, and SimCity. EA has many more franchises that it owns.

By contrast, Activision Blizzard invested in the innovative toy-game hybrid Skylanders. As a result, Activision Blizzard has a new billion-dollar franchise with more than 100 million toys sold. Riccitiello did a lot of the right things in his quest for the blockbuster game that would make EA great. They just didn’t all pan out.

The road to today’s EA

With consumers, EA’s games remained popular. But it occasionally ran into the buzz saw of public opinion. Many hardcore gamers hated the ending of Mass Effect 3, so much so that EA redid the ending in subsequent downloadable content. This got EA branded the “worst company in America.”

Some fans hated how EA charged for downloadable content that became available on the same day as a game’s launch. They felt that was nickel-and-diming them. And the haters came out again when EA’s servers failed to keep up with demand for the always-connected SimCity. In each of these incidents, Riccitiello took his share of the blame. But those things were minor compared to whether EA met its financial targets.

In his going-away message, Riccitiello said the decision to leave EA was all about his accountability for the shortcomings in financial results. Those results are at or below the guidance EA issued to Wall Street, and EA has fallen short of the internal operating plan it set a year ago. He said, “And for that, I am 100 percent accountable.”

Riccitiello reminded everyone that EA is No. 1 in mobile, the fastest-growing video game market. But it has had to adapt to swift changes in that business as well, as free-to-play business models now rule the business. These changes have leveled the playing field in mobile, giving tiny developers the chance to launch hit titles on an equal footing with giants such as EA. As big mobile hits for EA, Riccitiello cited The Simpsons: Tapped Out, Real Racing 3, Bejeweled, Scrabble, and Plants vs. Zombies.

It’s easy to name many big hits in mobile — Angry Birds, Temple Run, Cut the Rope, Tiny Wings, and CSR Racing — that became huge entertainment properties without the help of a big publisher. (EA did play a role in the beginning of Angry Birds, which was published by Chillingo, which subsequently was acquired by EA. But to say EA had a hand in the success of Angry Birds is a stretch). While EA is successful in mobile, so are many other companies.

“We were facing a world going through unbelievable change with the rise of smartphones, social networks, and more recently the iPad — each of which has turned out to be a platform where gaming is the No. 1 platform,” he said back in 2011.

EA is still waiting for its position in mobile games to pay off in a big way. It is part of a huge stake that EA has in digital games, but the payoff has yet to arrive. Riccitiello had suggested that digital games would help make the console boom-and-bust less cyclical. But here we are again, in a market trough, where game sales on the traditional platforms are starting to decline, and digital games are not completely offsetting that decline.

A spokesman for EA said, “It’s difficult to overstate how important the mobile segment is and how deeply it connects to PC, console platforms. EA’s leadership in mobile is a big strategic advantage for our brands and our profile on other platforms.”

EA is investing in games for the next generation of game consoles. But that’s another promise of something good, just around the corner. Investors have heard that story since 2007, McNealy said.

“Everyone fails,” he said. “Everyone falls down. Everyone loses a game or gets a bad grade.” When that happens, fail well, Riccitiello said back in 2011.

“I would argue we failed well,” he said. “We are students of our own failure. We used our failure to shape and impel us to a better strategy. One that we believe will ultimately succeed in ways that our previous strategy, even if perfectly executed, could never have done. … Trust me. Sooner or later, you’re going to get knocked on your ass. Will you fold? Or will you fail well?”

EA’s board finally lost patience with Riccitiello. EA’s stock price had been battered by the worldwide recession in 2009, and it never recovered. For the past decade, results have been flat. And Riccitiello was never able to get the stock price back to the level when he joined it.

It had stopped believing in the words that Riccitiello articulated so well in his 2011 speech. The end came swiftly. Riccitiello made a decision about something important on Friday, according to a source familiar with the matter. On Friday afternoon, Riccitiello met with Probst, who just became acting CEO again. On Monday afternoon, EA announced that Riccitiello had stepped down.

What’s next for EA, and who will be its next CEO?

Probst has the task of finding the next chief executive. As head of the U.S. Olympic Committee, Probst isn’t likely to stay in the job long himself. The natural candidates from EA’s internal team include Peter Moore, chief operating officer; Frank Gibeau, head of studios and executive vice president; and Dave Roberts, chief executive of PopCap Games.

But EA could reach outside for other industry leaders as well or pull someone who is steeped in the new digital gaming economy. EA has a lot of challenges ahead. McNealy said, “There are going to be more changes. They are not likely at the right size for where the bigger game industry is going.”

Ben Schachter, an analyst at Macquarie Research, said in a note that EA’s successor will have to contain costs and consistently deliver against expectations.

Clearly, the board isn’t going to be patient. EA has struggled and run in place for some time. This has an opportunity cost as rivals show how much better things can be. And whatever happens with the next-generation consoles, EA’s new chief will be heavily dependent on the execution of the plans that Riccitiello put in place. If he bet correctly, then EA will be golden.

An EA spokesman said that when you look at the demos for EA’s next-generation games, “You better be wearing a diaper.”

EA also says that the upcoming universal games platform, conceived by chief technology officer Rajat Taneja, will make EA’s popular Origin digital downloading service look like the tip of the iceberg on EA’s digital strategy.

Whomever EA chooses, Riccitiello says he will be rooting for them. In his farewell note, he said, “In a few weeks, I will be leaving EA physically. But I will never leave emotionally. I am so incredibly proud of all the great things you have done, and it has been my honor to lead this team these past six years. After March, I will be cheering wildly for EA from the sidelines.”

[Photo credits: Dean Takahashi, EA, Fox, and UC Berkeley]

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More