Slavery isn’t a new topic. We’ve read about it in books and watched countless films on it — 12 Years a Slave was a three-time Oscar winner this month. But we’ve barely touched the subject in games.

Thralled, an interactive thriller coming exclusively to Ouya this fall, broaches it head-on — and from the perspective of a woman, no less. A mother.

“We want to explore how the relationship of love between a mother and a child — which I believe is the utmost expression of love, that of a parent for her children — is conditioned through the extreme circumstances of slavery,” Thralled’s lead developer, Miguel Oliveira, told GamesBeat in a phone call.

“I or any of my teammates, we wouldn’t be able to depict what the violence of slavery is like. I don’t feel comfortable depicting such things as slaves being flogged because I’ve never been through that. I can’t understand how it feels. But I can definitely understand what the love between a mother and a child is because thankfully, I have great parents. … I can understand what that relationship is. So that’s kind of how we’re framing this topic, through a lens that everybody can understand.”

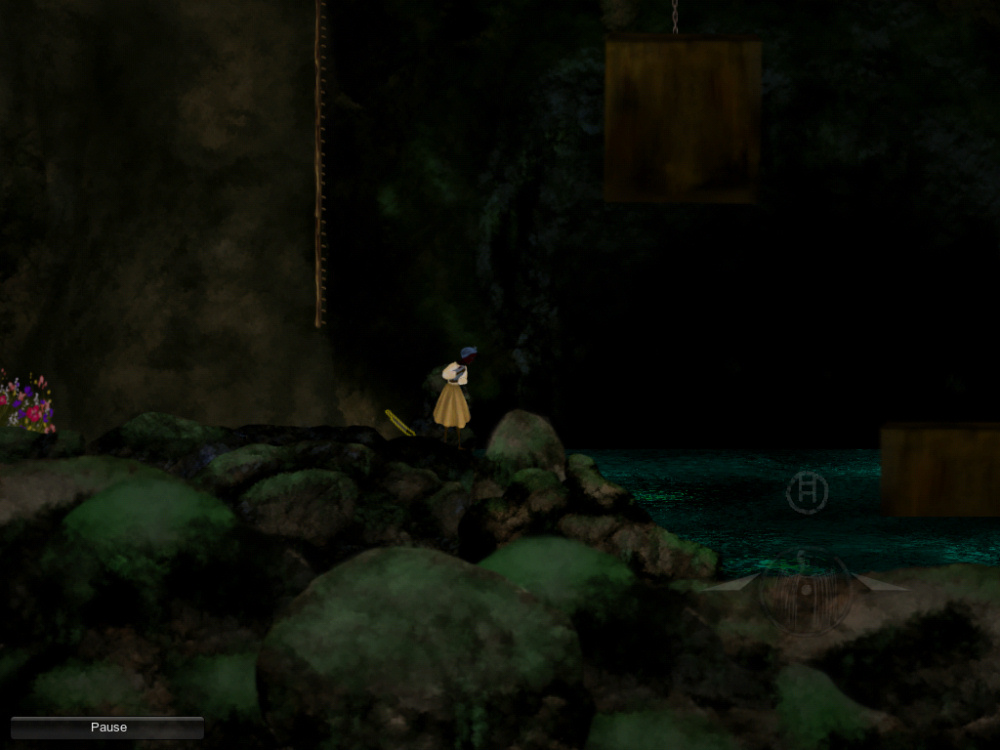

In Thralled, players control Isaura, a runaway slave in 18th-century colonial Brazil who flees into a nearby forest. There, a shadowy figure stalks her and her son. Players must find a way to bypass the forest’s natural obstacles, but that often means putting down her baby to climb ledges or other platforms with her whole body. Left alone, he’ll start to cry, which alerts the shadow watching them. Without Isaura’s protection, it will try to close the distance between them and steal the child.

This figure is representative of the slavers who are pursuing Isaura, but it’s also her own reflection, explained Oliveira. “She’s basically chased by this reflection of herself. And what that represents really is we’re trying to base the visuals of the experience around cultural references that would relate to the character.”

The shadow figure — a dead version of the main character — originates from the Congolese idea that the world of the dead was a reverse image to our own (think the dual worlds of Guacamelee, Drinkbox Studios’ action-platformer from 2013), existing beyond reflective surfaces such as mirrors and water. The skin of the dead appears white, the opposite color of the living’s — almost like they’re ghosts coming from the other side. But saying too much about what this means in Thralled would give the experience away.

Oliveira and his team have integrated other cultural aspects into the visuals. “A lot of the props that we choose to represent are directly taken from research about Congolese culture and about Brazilian culture at the time,” he said. “… And that’s a challenge because Congolese art was mainly focused on ceramics. So they didn’t do as much painting and whatnot.”

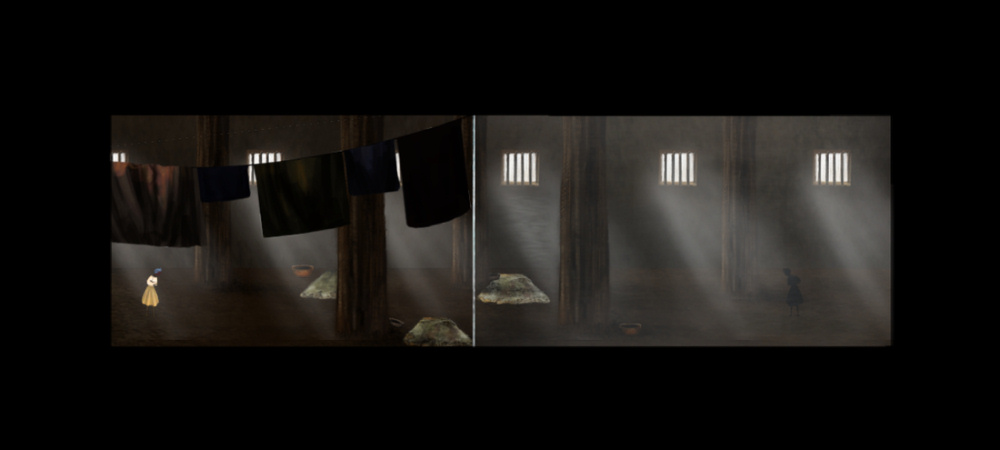

The environments themselves feel “big” and “oppressive” in relation to Isaura. “We’re trying to make her feel vulnerable,” Oliveira said. “Look vulnerable, move vulnerably. So that contrast is what we’re trying to focus on when it comes to art and depicting what’s going on in the experience.”

Thralled is engaging emotionally, but it’s tough to experience. Oliveira, who was born and raised in Portugal and came to the United States for college four years ago, feels passionately about how people remember this time in history.

“What really baffles me is that in school and in popular depictions of Portuguese history, the topic of slavery is never really — we never really talk about it. And I think that to avoid such a big part of our history is really a mistake.

“… [Interactivity] is really a way to make these sorts of difficult topics accessible to a wider audience, to make them understand and empathize with the victims,” he said. “Because that’s really what’s lacking is empathy between people. That’s where I feel most of the issues in our world come from — is the lack of understanding for other people.”

Oliveira said feedback so far at the Game Developers Conference this week in San Francisco has been that these gameplay sections are too difficult — you don’t have enough time to escape the shadow figure. “And the problem with it being too hard is that people will lose the feeling of tension at each retry,” he said. “They will lose the fear of losing the baby. Because they can just restart right away, and that feeling of tension is lost because they know they will have another opportunity to go about what they were doing. And that is something that we definitely need to fix.”

But other details in Thralled help players feel more connected to Isaura and empathetic to the suffering she endures. They take part in the story — go through the motions and struggles with her.

“One of the mechanics is you can hold the baby, you can kiss the baby, you can caress the baby to make him stop crying,” said Oliveira. “… We really want the audience to feel that act of love. … So I feel that the simple act of pressing a button on the controller and seeing that happen as a feedback of your action … I think it has the potential of being powerful and makes you feel like you are doing it because it’s happening as a consequence of your action. We hope to make it in such a way that the audience really feels like they’re the ones holding the baby and in such a way that they care about the baby and want to protect the baby.”

The imagery of slavery is everywhere in this “metaphorical jumble” of Isaura’s memories: In one scene, players have to push a cart, which is what slaves used to transport sugar cane from plantations to the mills. Players hack through chains and rope with a machete — breaking free.

“I think that the feelings that most video games focus on, which is aggressiveness and competitiveness, are very primitive feelings,” said Oliveira. “They belong to the animal side of us. What I’m really interested in seeing, and what I think a lot of empathy games focus on is feelings that really characterize us as human beings. Feelings such as love and caring and all those things.

“Those are the things that make us human. And really what art is I think is the exploration of the human condition. It’s something that’s introspective.”

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More