Whenever you move in with someone, you have to get used to a whole laundry list of new things that annoy you about them. For my wife, my gaming habit seems to be the biggest point of contention so far. I think in her mind, being a serious gamer was something only kids and sad, lonely adults did. She’s since learned to accept that I game, but the fact remains that she just doesn’t get the appeal at all.

To her, gaming is a pointless exercise in unproductive repetition: I mash buttons and funny/weird/interesting things happen on the T.V. But at the end of the day, what am I really getting out of it? So I’ve been thinking about that a lot recently: Why do I game, and why is it so important to me?

There are a lot of potential ways to attack this issue. I bet the argument the gaming community in general would use is also the most controversial: that gaming is a new medium through which artists may express themselves, and therefore what we get out of it is what we get out of any art; and if you can’t see that, then you’re just a lame-wad who’s stuck in an outmoded way of thinking, and you should open your mind to the possibilities, man!

I think the debate over whether video games can be an art form — if so, how, and if not, why — is definitely one that needs to be explored in much more detail (I may even take a crack at it on this blog sooner or later). But honestly, I never started gaming to consume art, and if the world got together on one brief, shining moment of universal understanding and declared that — whatever our other differences may be — we all agree that gaming has never been before, is not now, and could never be an art form, I wouldn’t abandon gaming as a hobby; the deeper, philosophical question, “Whither goest thou, gaming?” isn’t one which plagues me in the middle of the night (except to the extent that anything said in olde-tyme English excites me terribly). It’s just not germane to the question of why I game.

So why do I game, and why is it so hard for someone like my wife to understand? She and I are not that different in our tastes otherwise, so why the major discrepancy in understanding here? Well, to really answer these questions, I had to go inside my head a bit.

The first game in my life to really hook me was an action-adventure game for the Atari VCS called, well, Adventure. (Those were simpler times.) Adventure has you take on the role of a valiant knight who searches a dangerous land for a magical chalice. Populating this bizarre elsewhere are three terrifying dragons which the Wikipedia has reminded me are named Yorgle, Grundle, and Rhindle. (Indeed names to strike fear into even the most hardened adventuring adventurers of Adventure!) Well…that’s the premise, anyway.

The first game in my life to really hook me was an action-adventure game for the Atari VCS called, well, Adventure. (Those were simpler times.) Adventure has you take on the role of a valiant knight who searches a dangerous land for a magical chalice. Populating this bizarre elsewhere are three terrifying dragons which the Wikipedia has reminded me are named Yorgle, Grundle, and Rhindle. (Indeed names to strike fear into even the most hardened adventuring adventurers of Adventure!) Well…that’s the premise, anyway.

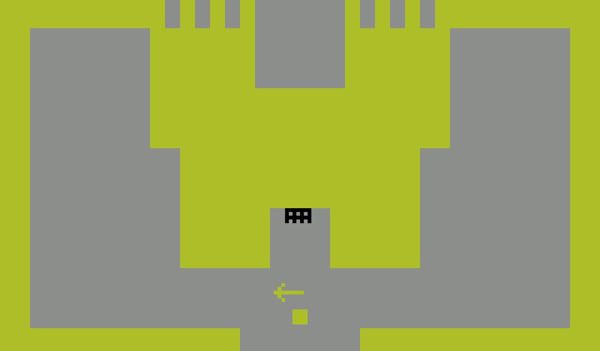

Really you’re a tiny square, and you maneuver through strangely shaped rooms inside and out of various castles in search of bizarrely shaped abstractions of real-life objects — keys, a sword, a bridge, and a magnet. The keys open the castles, the bridge allows passage through obstacles, the magnet attracts other objects, and the sword kills the dragons (which, in retrospect, look more like ducks than anything). Locating the magical chalice and bringing it back to your home castle wins the game.

Adventure also has three difficulty levels to choose from. The first difficulty level has only two dragons, a couple of castles, and one maze to navigate. Bumping the difficulty to the second level adds the third dragon, additional castles, a second, more complex maze, and a bat which can swoop in randomly and steal your items (occasionally making the game totally unwinnable). Putting the game on the third level would, in addition to all the stuff on level 2, randomize the location of every item — a maddening concept for my tiny, toddler-sized brain back then.

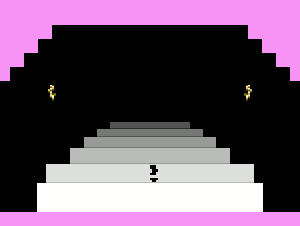

By today’s standards, Adventure would likely seem laughable even as a free-to-play flash game on some website. But in those days, where any graphics at all seemed a luxury, my imagination did an amazing job of filling in the blanks…of turning monochrome geometrics into real swords and keys and transforming a bland, emotionless maze into a place where danger lurked around every corner. I became that knight, and I felt real excitement and fear.

I would literally yell out loud when I saw those dragons and heard their ferocious roar. It felt real enough that the higher difficulty levels weren’t just too hard for me; they were actually too scary. (Cut me a little slack. I was like four.)

From that point on, gaming for me wasn’t just about solving the puzzle; it was also about being the character and actually overcoming adversity. In my mind, Link, Mario, Mega Man, Simon Belmont, and Ryu Hayabusa (I could go on, but I think you get the point) were all guys who were in real trouble, and I was going to become them to help them through their struggles.

From that point on, gaming for me wasn’t just about solving the puzzle; it was also about being the character and actually overcoming adversity. In my mind, Link, Mario, Mega Man, Simon Belmont, and Ryu Hayabusa (I could go on, but I think you get the point) were all guys who were in real trouble, and I was going to become them to help them through their struggles.

I used to expand on the stories in the games’ manuals, making up more intricate plots with my own dialog to explain why they were doing what they were doing; I imagined the characters were frustrated, scared, angry, or sad to be in their predicaments, and I felt real empathy for that; I felt a pressing need to see them through those situations and to safety.

I also love movies and books, so I realize that empathizing with a character isn’t restricted to gaming, but your participation in games sets it apart from other types of media. Even in a linear, side-scrolling action game, your limited control of a character’s movement still gives an impression of freedom: Mario has to move left to right, but whether he jumps to the floating platform, stays on course, or ducks into the next sewer pipe is up to the gamer, and this opens up the imagination to narrative possibilities which may be completely divorced from the designer’s intent.

So that’s what hooked me into gaming, but it doesn’t quite answer the whole question. To really understand why I continue to hold on to gaming like grim death, even to this very day, and even in spite of the many rolled eyes and exasperated sighs of my wife, you also have to understand a bit more about where I come from and what games have evolved to mean to me over the years.

Some of my earliest memories of elementary school are of playing make-believe games in a sandbox with a couple of friends. We made up this elaborate story about how we were actually aliens from a planet called “Weirdsville.” (I’m 100% serious) I think even in those early days, my friends and I knew we were different from the other kids, and as I recall, we kind of reveled in it a bit — kind of like how modern nerds do. But in those days, being nerdy wasn’t helpful to your image…not even a little bit.

These days, you’ve got porn stars and celebrities self-branding themselves as nerds to get cred with young people; geek-chic is hot. Back in the '90s, though, celebrities were most certainly not calling themselves nerds, and cool kids were absolutely not doing any of the nerdy things I was doing. And when you don't follow the cool kids, the consequences are dire. It doesn’t happen right away, though.

It’s all well and good to be a little weird when you’re in the first grade, but you’d better make up for it quickly because otherwise you’ll be branded a freak by the cool crowd. But I was oblivious to that truth, so I carried on acting “strangely,” talking about my fantasy worlds and endlessly bothering whomever I could with conversations about video games. Because, I thought at the time, everyone would want to talk about those things in never-ending, sickening, nearly pornographic detail, right? As surprising as it may seem, they did not. Boy, did they not.

In elementary school, I got a lot of shit from the other kids, but it rarely turned physical. I actually cannot recall any specific time that my nerdiness got me beaten up back then, though certainly there was often the threat of violence. Even so, I had enough run-ins with people who were quite willing to tell me exactly what they thought of my personality, physical appearance (I was also the fat kid), and dress that I was never under any illusion that I might be fitting in.

So why am I relating all of this in a post that was supposed to be about gaming? Why relate stories of bullying and social rejection? In my darkest hours, when it seemed that there was nothing good left in the world, there were games. Every day I could come home after school and escape inside a world where I was no longer on the lowest rung of the ladder. In games, you become the most important person to the story — the hero. And in that black-and-white existence, the hero must necessarily triumph; his battles can be won, and they can be won fairly.

You become strong, confident, you can go anywhere, and you can do anything. Inside my mind, I was felling monsters and evil armies, breaking corrupt empires, overthrowing mad tyrants, and all of it was not only possible, but it was probable. For every unbeatable bully out here in the real world, there were a thousand easily defeated Bowsers, Mother Brains, Draculas, or Sephiroths in the games. Becoming Mario, Samus, Alucard, or Cloud, I could bring a sense of order to the world, even if it was just a binary world inside a game machine.

You become strong, confident, you can go anywhere, and you can do anything. Inside my mind, I was felling monsters and evil armies, breaking corrupt empires, overthrowing mad tyrants, and all of it was not only possible, but it was probable. For every unbeatable bully out here in the real world, there were a thousand easily defeated Bowsers, Mother Brains, Draculas, or Sephiroths in the games. Becoming Mario, Samus, Alucard, or Cloud, I could bring a sense of order to the world, even if it was just a binary world inside a game machine.

But it wasn’t just the grandiosity of the experience that attracted me. In a game like Final Fantasy VII, for example, the world is so intricate and expansive that you can literally spend a hundred hours in it (if you take your time and do everything). For a boy of fifteen who feels as if the real world is set against him, the feeling of slowly making your way through FFVII, bringing together a rag-tag party of heroes and heroines, and setting out on adventures, was an epic dream; I went everywhere, I talked to everyone, I did everything, and I felt connected to that world in a way — healthy or not — I couldn’t feel connected to in this one.

The people I met there felt real enough to me, and I invested in their stories such that I felt real emotions for them as they suffered or triumphed, and it all mattered because I was there, with them, controlling the outcome of their story. In short: I felt like I mattered there, where in the real world I felt only ignored and rejected. And Final Fantasy VII is just one of dozens of games where I felt that kind of connectedness and belonging.

My friends from those days were all gamers, too, and it seems like most everything we did revolved around gaming in one way or another. When we talked in school, we talked about games, and when we hung out after school, it was usually to game together. Games gave us a common reference, a kind of code that we could talk through. When we all played the same RPG, we talked about it every day; where were we now? Had such-and-such boss given anyone else trouble, too? Did anyone else get that great item or find that crazy secret?

And when we gamed together after school, it brought us even closer together. I can’t say how many hundreds of hours we spent playing GoldenEye for the Nintendo 64 together. We trash-talked, we laughed, and we bonded with each other just as any group of guys who play sports together might. (Though, to be fair, it didn’t help much with my physique.) Far from gaming making us into freakish shut-ins who scorned the sun, we were learning to be competitive and work together just as any “real” sport might. (Well, that sun-scorning thing was probably true.)

In those days, gaming just wasn’t the popular pastime that it is today, and I think it made us feel special to have these experiences to share with each other. It empowered us that we knew something no one else knew (or, at least, that’s how it felt to us at the time). We couldn’t force the bullies or the popular kids to accept us, but they couldn’t stop us from forming our own community. While pop culture made us the butt of the joke on every sitcom, we went ahead and created our own subculture; even if no one ever understood us, we got it.

Even now, after all these years, gaming is still where I go to when I really need to get away. When I’m having a bad day or feeling stressed, gaming is still my first go-to for relief. Now that my real life is no longer so destructive and chaotic, my sense of empathy with gaming characters has necessarily weakened, but I do still get invested in my games.

I still want to be there with the characters, and through the resolution of their problems, I still feel a sense of personal accomplishment that may be difficult for a non-gamer to truly understand. And I still feel a sense of community in gaming. Some of my best friends now were my best friends when I was a kid, and I feel like we’ve managed to stay together partly because of our shared love of gaming. Making new friends my own age is also easier: If I meet someone who’s a gamer, we instantly have a repertoire, a common vocabulary, and many shared digital experiences we can reminisce about.

When you tell the world that you’re a gamer, it can be difficult to also communicate why you game without looking a bit silly. Because even if gaming has become more accepted by mainstream culture, some people still see it as a waste of time. And perhaps for a lot of people, gaming really is nothing more than a way to kill time on a rainy day. (I’ll admit, games can and do fill that function quite nicely, too.) But my life has been intertwined with games in a deep and profoundly personal way: It’s taught me to imagine worlds beyond our own and to expand my creativity in ways I’m not sure I ever would have otherwise.

Gaming gave me a place to escape the real-life monsters of the world…to let myself go and forget how much I desperately hated being me. Gaming gave me a community and an identity where the rest of the world seemed desperate that I should have none. And gaming, even now, gives me my own space to go to when I need to relax and burn off the stress of the real world.

So…yeah, it’s kind of silly and childish sometimes, and maybe that time really could be spent learning to play the keytar, or study phrenology, or whatever it is I’m supposed to be doing instead. But gaming was there for me when I needed it, and it’s not easy to let go of now after all this time invested. So while I don’t expect everyone to take to games, or to love them like I do, I hope at least some people can try to understand the reason why I game — why I think a lot of us game. Maybe if they can do that, they’ll be a little more forgiving if I seem a little too into gaming.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More