OK, so it’s pretty funny seeing someone fall over after trying a virtual reality headset for the first time. But with companies like Facebook, Valve, and Sony all pushing to bring their own VR solutions to a mainstream market — worth an estimated $30 billion by 2020 — maybe we should have more concern for what the technology is actually doing to our bodies and minds.

It’s true that every new technology comes with new fears — and often they’re completely unfounded. Some folks blamed the wireless radio for distracting children from their school work back in 1936, and Edison’s first electric power plant ran for two years before the American public actually trusted it.

But VR is a technology that will shortly explode into the mainstream — with people potentially immersing themselves for significant parts of their day — and there’s not been much discussion about the potential physical and mental health ramifications.

So what are the potential risks, and how real are they? I’ve picked through some of the academic papers on VR and talked to experts across a variety of fields to find out more.

Focusing on a virtual world

In order to understand some of the potential problems with VR, it’s important to appreciate the biological mechanisms at work when you view a stereoscopic image.

Looking at any stereoscopic display is counterintuitive. That’s because there are two mechanisms at work when you look at something in the real world, and these need to follow different rules for VR.

In the real world, our eyes work to both focus and converge on a point in space when we look toward it — it’s a natural reflex called the accommodation-convergence reflex.

“The distance you need to converge your eyes to and the distance you need to focus your eyes to are the same distance,” explained Marty Banks, professor of optometry, vision science, psychology, and neuroscience at UC Berkeley in a phone call. “The brain has coupled these two response together — that’s why it’s called vergence-accommodation coupling. It makes total sense in the world we live in.”

Above: Oculus Rift is heading to the mainstream soon, thanks to massive financial backing from Facebook.

With VR, though, our eyes always focus on a fixed point while trying to converge or diverge toward objects that can appear either nearby or distant. This mismatch is known as the vergence-accommodation conflict, and it’s the reason many people experience visual discomfort when using a VR.

“We believe the brain has to fight against its normal coupling to handle that problem, and that makes some people uncomfortable,” said Banks. “That makes some people’s eyes tired. There are even some cases where it makes people nauseous; it gives them a headache.”

Banks told me about claims — largely unfounded so far, in his opinion — that people might experience long-lasting changes in the coupling between vergence and accommodation due to VR headsets. “I don’t believe that,” he said.

“Those couplings are fairly plastic. You can learn to change those relationships. The one you have naturally, I think you’ll just go back to that when you take the headset off and look around the room and give your eyes a second to adjust.”

But our experience of VR so far hasn’t included sustained use of HMDs for extended periods of time, especially by a large community. We’re heading into unknown territory, and even experts like Banks can’t be sure what we’ll find.

Heading down the rabbit hole

“Whenever you introduce something that is new that people might be using for a long period of time, obviously you should be on the lookout for potential problems,” said Banks. “That’s just being sensible.”

I asked whether using VR systems for long periods of time could result in long-term vergence-accommodation problems.

“Well, we don’t really know,” he said. “I don’t think there’s a smoking gun out there, but what we don’t know is long-term use — let’s say 12 hours a day — would that have any long-term effect? I doubt it, but I can’t prove that to you scientifically.

“I think that’s something we want to keep an eye on.”

Development builds of Oculus Rift have been around since late 2012, and early adopters have already reported ocular problems with extended use. While these reports aren’t especially widespread, they’re enough to raise concerns.

Reddit user Abore reported persistent eye after using the Oculus headset. “My left eye has been giving me shit due to the Rift,” he said. “Specifically the muscles behind it. Definitely eye strain and it persists hours after I take the Rift off. I’m taking a week off to let it recover.”

And Lee Hutchinson of Ars Technica noted sustained visual effects after long sessions playing Elite: Dangerous on Oculus Rift’s DK2 build.

“With the Rift fitted properly against my face,” said Hutchinson, “the normally too-tiny-to-see pixel grid of the display is clearly visible, and staring at that grid for hours at a time is burning the pattern into my retinas, like a Pac-Man maze making a permanent impression on a CRT monitor.

“I can still faintly see this grid right now when I squeeze my eyes shut, in spite of the fact that I’ve had a solid night’s sleep. It’s superimposed over the usual retina noise I get when I close my eyes—or perhaps it’s better to say that it’s a very prominent part of the noise.”

Newer versions of the Oculus headset have a higher resolution display, but this is still an interesting side-effect of sustained use. I asked Marty Banks about it, but he couldn’t nail down what the cause could have been.

“You could get an after-image,” he said, “but when you get an after-image and then look out at an illuminated world they usually go away within a few seconds to, at most, a minute or so. That sounds — if it persisted longer than a few minutes — that it’s not an after image. That strikes me as odd — I’ve never seen that myself.

“I’m sure he’s not making it up, but I don’t have a bucket to put that in.”

Heavy machinery

Oculus is already aware that using VR can cause problems with hand-eye coordination, and it warns Oculus Rift users about potentially dangerous symptoms of VR use.

“Do not drive, operate machinery, or engage in other visually or physically demanding activities that have potentially serious consequences — or other activities that require unimpaired balance and hand-eye coordination — until you have fully recovered from any symptoms,” reads the health and safety warning.

Albert “Skip” Rizzo — a long-time virtual reality expert and the director of the University of Southern California’s medical virtual reality department — explained that potential hand-eye coordination problems are likely linked something called past-pointing. It’s a perceptual phenomena where people fail to point accurately to an object in space, first described by ophthalmology pioneer Albrecht von Graefe. It’s traditionally seen in patients with strabismus (or “crossed eyes”) caused by muscle paralysis but also in pilots who’ve been using flight simulators.

Above: Soldiers at Fort Bragg before entering a simulated battlefield environment.

“If you’re in a simulation, your brain adapts to the constraints of that simulation,” explained Rizzo. “If you do if for a long time, immediately you get out of the simulation, for a brief period of time, your brain has to re-adapt. If you reach for something you may reach past it because VR may affect your perception of objects at a distance.”

Past-pointing can significantly affect you ability to carry out everyday tasks. Rizzo explained that he always takes care with participants in his VR studies, even arranging cab rides for participants, rather than letting them drive home.

People using VR headsets at home won’t have anyone looking over their shoulder and watching out for them. There won’t be anyone to stop them jumping in the car and driving down the highway after a long gaming session, and that’s something they really shouldn’t be doing.

Despite the potential dangers, though, Rizzo says that the disorienting effects of VR are only short term.

“Do I think it’s long-term? Do I think it’s something that changes people for hours on end?” he asked. “No way!”

Interestingly, Oculus particularly advises against children aged 13 and over using the system for prolonged periods of time, saying it could “negatively impact hand-eye coordination, balance, and multi-tasking ability.”

Rizzo is pretty sure why this additional warning is in place, though. “I certainly think they’re covering themselves,” he told me over the phone, “as any companies making these devices would be smart to do.”

VR and kids

Oculus Rift’s health and safety warnings explicitly state that kids under 13 shouldn’t use the VR system.

It’s likely linked to fears of stereoscopic images harming children’s still-developing eyesight. They’re the same fears that arose when Nintendo’s 3DS handheld debuted in 2011, and they won’t go away.

Dr. Tom Piantanida wrote a review of HMD safety back in 1993 and suggested that VR headsets could trigger latent visual problems in people with intermittent exotropia — a condition quite common in young children where one eye sometimes turns outward.

Piantanida argued that HMDs and other stresses can trigger episodes of double vision in these children, which can then lead to permanent visual changes.

“The visual system attempts to overcome the inconvenience of double vision by suppressing one of the images,” said Piantanida. “This suppression, if it occurs in very young children and if it is sustained, can lead to permanent visual changes of the type commonly called amblyopia or ‘lazy eye.’ Thus, in a small number of very young children, HMDs … have the potential for triggering latent visual anomalies that can produce permanent visual changes.”

Marty Banks remains sceptical about this risk, but he says we still need to take care.

“That would be a smoking gun,” he said. “I haven’t seen such effects myself. I’ve spent years looking at stereoscopic images, and many of my students have spent hour upon hour and none of us have had any effects like that. But kids are different; they’re tough to collect data on.”

“We don’t have a large database of children that we’ve looked at and seen what effects there are,” said Banks. “You’re a little less certain saying there’s no problem with kids. But I haven’t seen anything that stands up yet.”

Professor Peter Howarth, an optometrist and expert on stereoscopic displays based at Lougborough University in the U.K., doesn’t believe that there’s a significant risk with stereoscopic images and kids. In fact, he’s pretty sure that stereoscopic images — if presented correctly — are actually helpful to children suffering with intermittent exotropia, by forcing them to use both eyes together.

“The concern seems to be that there is a ‘one-in-a-million’ chance of there being an adverse reaction,” he said, talking about the Nintendo 3DS back in 2011, “and the counter-argument is that there is a far greater probability of the use of the 3DS being beneficial. The logical conclusion to all of this is that, far from warning people about the danger of children using the 3D system I have just bought my daughter, Nintendo could argue that the playing of the games could be of benefit to children!”

I contacted Howarth to ask if he was as confident about potential problems with the stereoscopic displays in VR headsets, especially given Oculus’ clear warning about under-13s.

“My confidence comes from the fact that orthoptists treat muscle deficiencies by using such stimuli,” he told me via email. As for the warning, he said, “I presume that Oculus are covering themselves — [the] same with Sony et cetera.”

However, he did point out that HMDs are open to problems of misalignment between the user’s eyes and the physical position of the headset’s optics. A 1997 review of VR health and safety reported that this can lead to visual discomfort symptoms, transient heterophorias — where one eye points to an unnatural position at rest — or muscle imbalances. Again, the author noted these changes are thought to be temporary, but that’s without considering the long-term, extended VR use we’ll shortly be witnessing.

I asked Howarth about the idea of using VR for extended periods of time — say, 12 hours a day. “It’s not ideal,” he told me, “for lots of reasons. The primary ocular reason is that, because the screen will be at the same distance, the stimulus for accommodation is constant throughout.”

Virtual Reality vs. the real world

If you’ve ever seen Tetris blocks when you shut your eyes, you’ve experienced Game Transfer Phenomena, according to psychologist Angelica Ortiz de Gortai, based out of Nottingham Trent University, U.K..

She thinks that the mainstream use of virtual reality headsets will bring an increase in the occurrence of GTP, something that’s largely restricted to the gaming community right now. Her research has already described GTP symptoms like seeing objects turn into clusters of pixels, hearing sounds from games when you’re falling asleep, or even swerving to avoid Battlefield-style ‘land mines’ on the highway. With the increased immersion offered by VR experiences, GTP is potentially going to be a wider problem.

“Individual susceptibility is crucial,” she told me via email, “but I believe that GTP will become more common as technology becomes more persuasive and stimulates a larger number of sensorial channels.”

For Ortiz de Gortari, the use of VR may actually change the way we define reality, and we’ll find our brains confusing virtual and physical events.

“As virtual environments facilitate richer perceptual, spatial, and emotional experiences it will be easier for us to find ourselves in situations where suddenly we make mishaps confusing virtual events from the ones in the physical world,” she said. “The consequences may depend of the intensity, frequency, [and] the circumstances where these mishaps occur, and how each individual interprets these experiences.”

One study of extended VR use seems to back up these claims. University of Hamburg researchers Professor Frank Steinicke and Dr. Gerd Bruder put a subject in an immersive VR environment for 24 hours, with shorts breaks every two hours.

As well as feeling nauseous at times, the research subject become confused between the real and virtual worlds. “Several times during the experiment the participant was confused about being in the VE or in the real world and mixed certain artifacts and events between both worlds,” reported Steinicke and Bruder.

The problem of virtual events and objects impinging on real life has potentially serious repercussions. While GTP incidents are usually momentary, if someone experiences them while operating machinery or driving, they could prove fatal. “Driving requires split-second decisions and the reading ahead of how other road users are behaving,” Peter Wright, the managing director of U.K. law firm DigitalLawUK told GamesBeat last year. “If that ability is impaired in any way, reaction times could be increased with potentially fatal consequences for other road users.”

Wright said it was conceivable that tests could be introduced to spot GTP in drivers if cases occur where it’s proved to have caused incidents, accidents, or even death. “Currently, such tests are focused on alcohol and drug use, but if a driver were asked to take a few paces, stand on one leg, [and] answer a few questions, it may establish if the driver is experiencing Game Transfer Phenomenon,” said Wright.

Those already confusing reality …

Virtual reality has been used in therapeutic settings for over 20 years, and it’s widely employed in helping sufferers of post-traumatic stress.

Back in 2003, though, Albert Rizzo identified potential ethical problems for psychologists using virtual reality therapy. Rizzo’s main concern was that people with an existing disconnect between fantasy and real life may find that virtual reality causes further mental problems — perhaps even leading to paranoid delusions.

“Difficulties in detecting experiences between real and virtual environments could lead to misinterpretation of sequences of events, and/or the development of paranoid delusions,” warned Rizzo at the time.

Above: There’s been very little research on long-term extended VR use.

When I spoke to Rizzo recently, he explained that his position had changed somewhat based on more recent research. There have been studies where VR has been used with people with schizophrenia, he told me, and it hasn’t caused any kind of break with reality.

But the field is still young, and few studies have explored the effects of using VR for regular, extended periods of time. It’s something that Rizzo is aware of, and he acknowledged that more long-term studies are needed as the technology enters mainstream use.

“As people make things way more compelling and you’re engaged for two, three, four hours [at a time],” said Rizzo, “that’s when it’ll be interesting to see what happens. It’ll need to be studied.”

Addiction to a virtual world

Video game addiction is already a concern for many, despite the fact that the American Psychological Association doesn’t yet recognize it as an official mental disorder.

With the relatively cheap option of immersive virtual reality, there’s a worry that living with a virtual headset on will be preferable to taking it off, at least for some people.

Rizzo previously noted that this could be particularly tempting for people suffering from mental health problems. “The lure of an alternate environment would be hard to predict for individuals who are faced with the daily struggle of coping with visual or auditory hallucinations,” he said back in 2003. “As such, these individuals may be at higher risk for negative behavioral and psychophysiological responses.”

But anyone could potentially find the temptations of VR hard to resist. Speaking to Rizzo, he referred to isolated cases where gamers have died, or caused the death of others, through gaming immersion to the detriment of self-care. Just recently, a Chinese gamer died after a 19-hour session playing the massively multiplayer role-playing game World of Warcraft.

With VR, the potential for getting hooked is heightened.

“There is that potential [for addiction],” said Rizzo, “and there always has to be an appropriate level of caution with anything like this.”

Dr. Andrew Doan — the head of addictions & resilience research for the US Navy — recently reported on a case of addiction to Google Glass — a wearable device that layers internet functionality over the real world. While Google withdrew its $1,500 Google Glass from sale recently, it was available long enough for one US Navy serviceman to dream about it and experience severe withdrawal symptoms when it was taken away.

I asked Dr. Doan — himself an ex-gaming addict — if he thinks we’ll start seeing similar examples of virtual reality addiction.

“Because virtual reality is more arousing to the brain and neuroendocrine system, we may see more problems with addiction and abuse as devices become accessible to more people,” he told me via email.

As with so many aspects of VR, it’s something that’s going to need further research and attention as the technology explodes.

“The Google Glass case was only one case and we need more research and data [in these areas],” said Dr. Doan.

Real life hazards

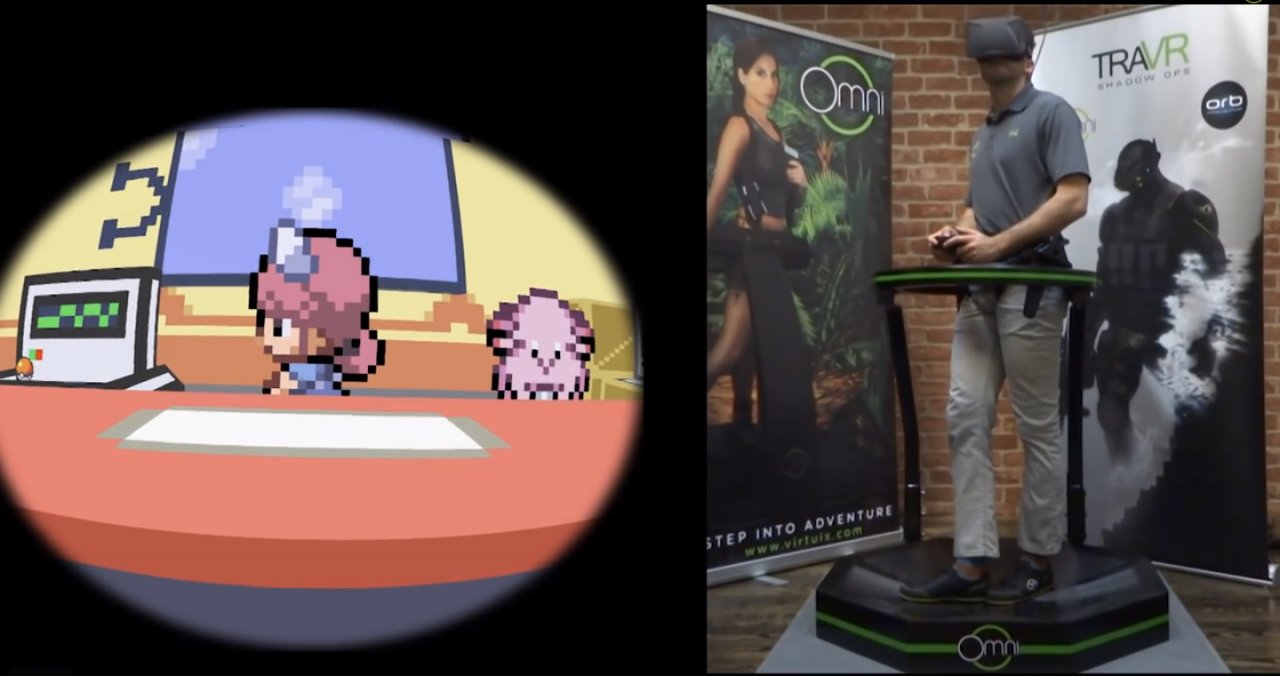

One of the biggest potential hazards from VR is also one of the most basic. It’s the fact that you’re wearing a hulking great headset over your eyes, and you can’t see your own surroundings.

“I’m sure something will happen,” said Albert Rizzo. “One thing that everyone overlooks with this stuff is when you’re completely immersed, you’re also disconnected from physical reality. There’s a high chance you’re going to fall or something.”

He recalled the wave of broken TV screens when the Nintendo Wii first hit the market. People weren’t used to swinging a controller around and got way too exuberant, and Nintendo had to issue stronger wrist straps along with firmer playing guidelines.

Immersing yourself in a virtual reality — especially one that includes body tracking — can, and probably will, lead to accidents in the home. The fact that you’ll likely be connected to your PC or game console with a bunch of wires will make it all the more risky.

“If you’re in a very compelling game in an HMD, there’s a good chance you’ll forget where your feet are and trip over your cat,” said Rizzo.

“Or your kid,” I joked.

How the manufacturers see things

Oculus declined to comment on these issues, saying there weren’t conducting any interviews outside of trade shows. I didn’t have much luck with Sony’s Project Morpheus team, either.

After some deliberation, Sony declined to respond to the questions I sent through, citing the system’s anticipated 2016 launch date and saying it would be “a bit premature” to go into detail right now.

It’s a shame, but looking through the official Oculus resources at least gives some idea of the lengths the company is going to ensure it’s taking care with our health, whether that’s just for legal reasons or not.

Going forward, it’s clear that we’re largely stepping into the unknown. There has been very little research dealing with long-term extended use of VR headsets, and the early adopters of this new technology are almost the first wave of proper testers.

While there isn’t a single smoking gun that immediately jumps out, there are enough potential concerns to warrant monitoring the situation closely. And further research is definitely needed.

“Eye care professionals are aware that the visual environment for these people will be changing,” said Marty Banks, “so they’ll be on the lookout for signs that there is some problem.”

“To my knowledge, so far there’s nothing really substantiated that is causing great concern,” said Banks. “But I hope your article will convey the message that just because we haven’t seen evidence, doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t be attentive.”

That’s the hope.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More