Let me tell you about something I like to call the sweet science of hiding in lockers in Alien: Isolation.

It relies on timing and coordination. If you wait too long to hop into that nearby storage locker, a massive alien will see you and tear you to shreds. Staying in your deceptively safe compartment for a while is a great way to make the alien suspicious. Failure to lean back and hold your breath when prompted while the alien probes your locker door will result in the creature ripping you out and tearing you to shreds. Even if you jump in a locker at the perfect moment and execute any and all commands to perfection, the alien may still spot you, pull off the door, and — you guessed it — tear you to shreds.

If this is too vague, let me sum it up a little more clearly: Alien: Isolation is hard — very hard. It brought most of the 20 or so journalists at Creative Assembly’s Thursday press event in San Francisco to their knees at one point or another.

But it’s the reasons behind this intense difficulty that are the most interesting part of Alien: Isolation.

It feeds on players’ preconceived notions of exactly how a game and its characters should behave. We have all been conditioned over the last 20 years to expect certain features, but Alien: Isolation refuses to play along. Things that make sense everywhere else don’t work here.

The experience of rebuilding your expectations is a mixed bag. The fresh, challenging gameplay mechanics were exciting at first, but it loses its sharp edges after about the 80th death. The alien didn’t scare me when it attacked — it just annoyed me. It’s possible that doing something truly different could actually harm Alien: Isolation in the long run.

The traditional survival-horror setup

In Alien: Isolation, players take on the role of Amanda Ripley, the daughter of Alien protagonist Ellen Ripley. It’s been 15 years since Ellen’s brush with an alien, and Amanda is looking for clues as to her mother’s whereabouts and the fate of Ellen’s ship, the Nostromo. Amanda is transferred to the Sevastopol space station, where yet another 9 foot-long killing machine has taken up residence.

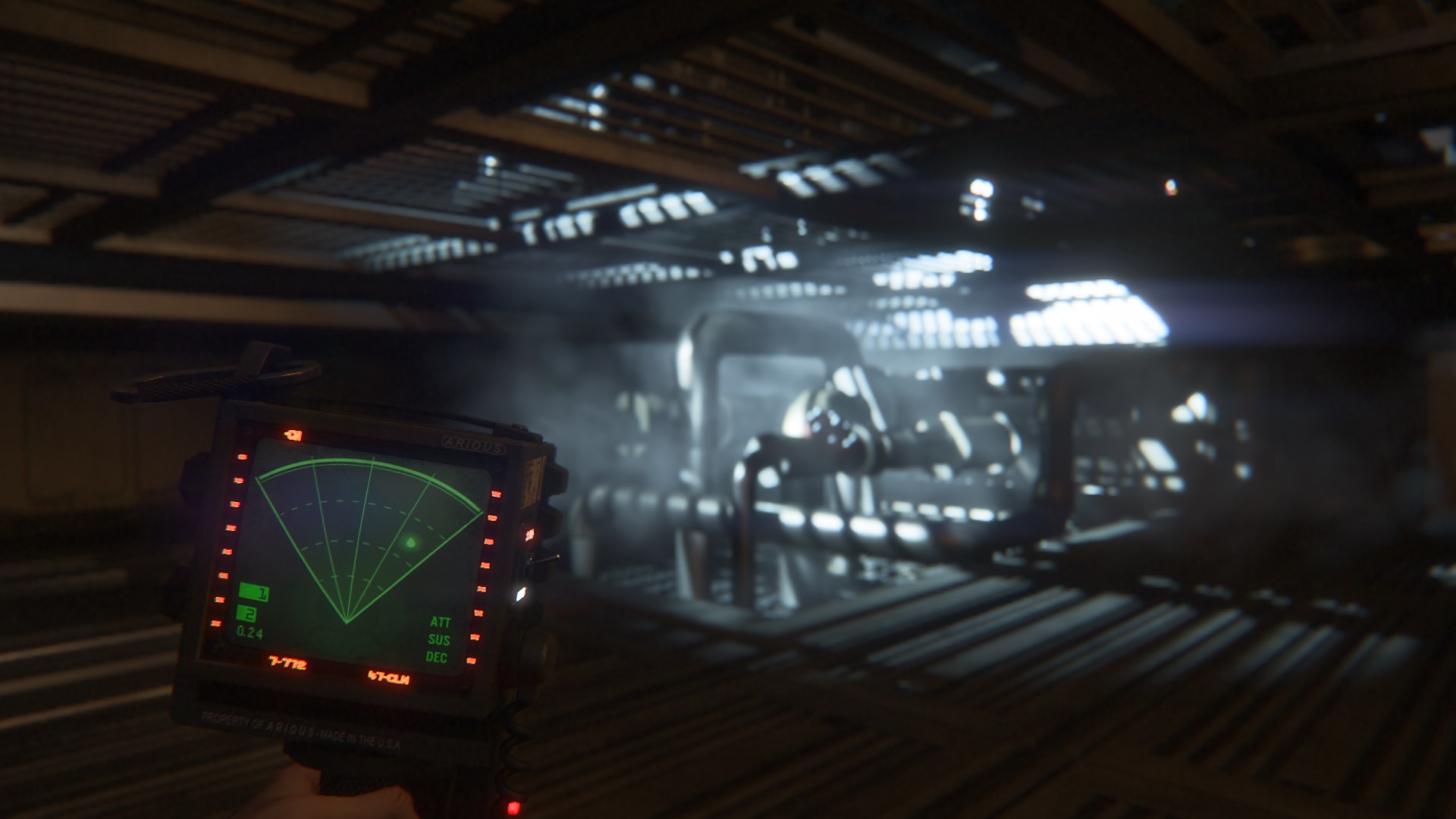

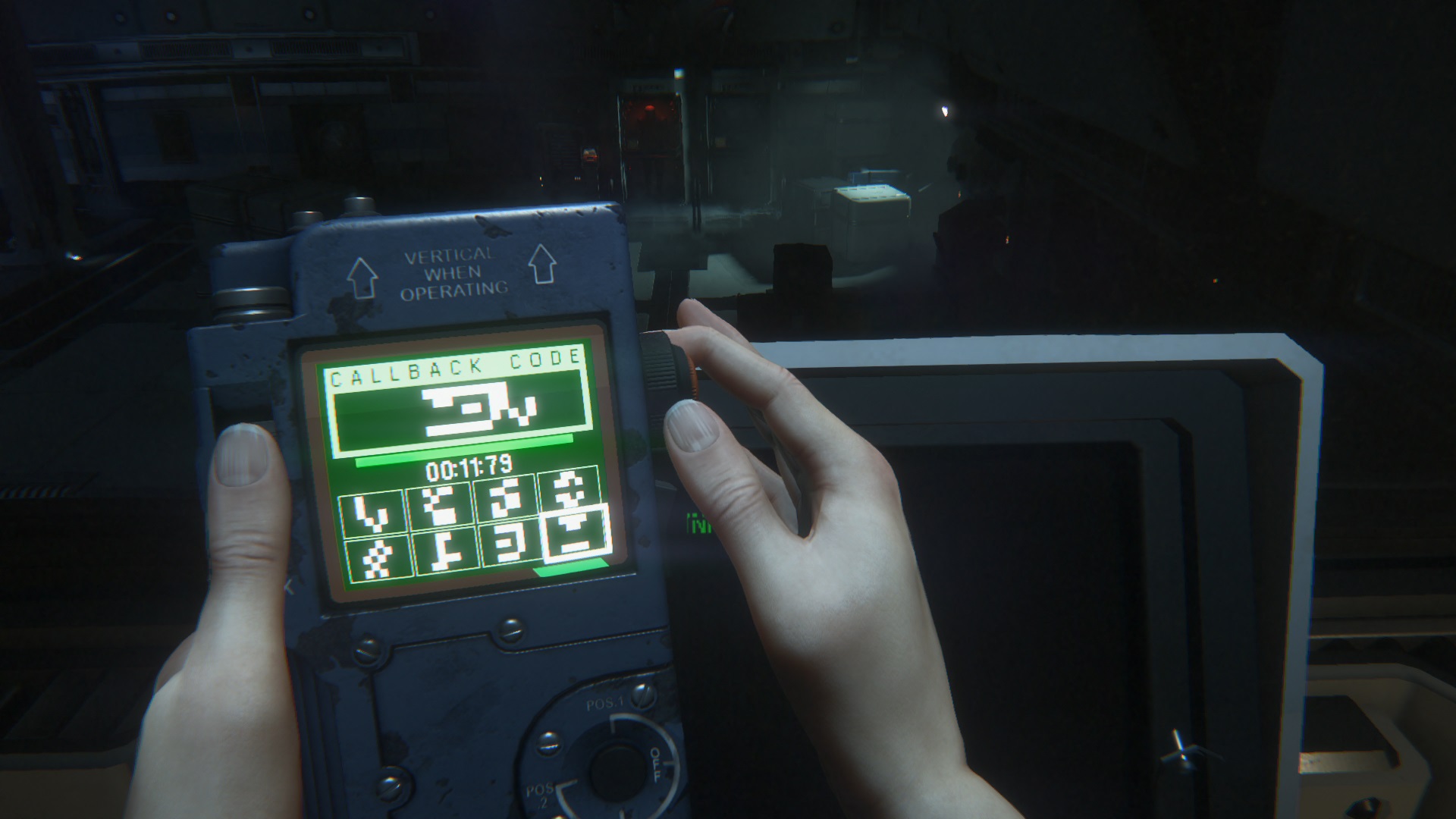

I felt comfortable taking control of Amanda. I had all of the usual survival tools: a flashlight, radar (in the form of a portable motion sensor), a map, and a sparse selection of weapons and supplies.

The world looked exactly as I expected it to. The dark, low-fidelity look of the space station triggered two familiar thoughts in my brain: This is Alien, and this is a survival horror game.

Isolation’s creative lead, Al Hope, told me in an interview that this was exactly the point.

“We took our cues from the first film, which really downplays the sci-fi in favor of a much more mundane, tactile world. I mean, people are still traveling through space and going into stasis and such. It’s definitely in the future, but there’s no sense that you are going to find this massive sci-fi gun that will solve all your problems, like in Star Wars or Star Trek,” Hope said. “They establish this in the first film, and I think it just naturally feeds into the horror.”

Nevertheless, the first time I encountered the alien, I blasted away at it with my revolver. I know the rules: This thing can’t die. If I could shoot it, the game would be over in 10 seconds. But that’s how I have been groomed to solve problems in today’s video games, so I gave it a try.

And it eviscerated me.

OK, I’ve learned my lesson. It’s going to take a little more finesse to make it past this creature. I will have to hide and utilize my tools properly to escape.

Now that you’re settled in, it’s time to crush your soul

I tried using everything in Amanda’s arsenal to confuse my foe. I threw a smoke bomb and attempted to walk past it. As it turns out, the smoke bomb blinds me but doesn’t really bother the xenomorph (that’s a fancy name for Alien’s alien) bent on killing me. It stuck a spine through my chest as I tried to sneak past.

The next gadget up was the noisemaker. I threw it, and the alien ran toward the noise. I walked triumphantly down the necessary corridor only to get that same spine in the chest. The alien checked out my noisemaker for a second or two, but he had wheeled around and spotted me as soon as I made my move.

I tracked down Hope again to ask him what gives.

“The most important thing we wanted to do was get the alien right,” Hope said. “He’s the star of the show. We wanted his behavior to match that of the original alien’s, and we spent quite a bit of time animating and matching the sound to his movements. If you alert him but break line of sight, he usually won’t attack — usually. He will definitely investigate your area though, even if you use a tool.”

That’s when it hit me. If this monster’s creator doesn’t know where it’s going, I have no chance.

The alien doesn’t follow any patterns. It doesn’t fall for your gadgets’ tricks, it doesn’t respect your hiding places as out-of-bounds, and it doesn’t follow any traditional survival-horror villain tendencies.

I expected the alien to travel at a consistent speed, which would give me the necessary time to slip past when it walked by me. It doesn’t. Sometimes it runs for no reason. Sometimes it walks painfully slow or stops on a dime and looks around. Hope would later tell me that the alien actually travels on through air ducts and channels both above and below the player, which enables it to travel from room to room in a way that seemingly denies the laws of physics.

I don’t even know when I am alerting the bastard. Games typically bombard me with cues when I am being too reckless, like yellow question marks turning red or some kind of sound or vibration hint. I could faintly feel and hear if the alien was walking near me. If the music suddenly gets loud and the vibrations go crazy, I know I am about to die. But that’s really about it.

The level design also plays tricks on players. Each level has multiple routes to and from the various rooms that Amanda must visit. This sounds like a positive in theory because it helps players to find more ways around the alien. My experience was actually just the opposite; I found that it simply provided the alien with more routes to chase me down and kill me.

And it isn’t just the alien that’s out to get players. The other humans on the space station are just as likely to shoot Amanda as they are to offer aid or ask for help.

Hope said that the development team really wanted to convey a sense of panic and disaster on the space station.

“These people are desperate to survive. I was inspired by War of the Worlds, by H.G. Wells, and the way people react in that crisis. When you come across a guy in the game, he might point a gun at you and say ‘Hey, you go your way and I’ll go mine.’ Some will be hostile or freaked out, and some will be a real asset.”

FYI: Your weapons work just fine on other survivors — if you choose to go that route.

The final slap in the face of modern gaming trends came in the form of save points. Alien: Isolation does not use checkpoints; players must find and use various save points located throughout the levels.

It sounds like a little hiccup. I didn’t even flinch when Hope told the group about this before leading us to our video game slaughter stations.

I was wrong. This makes a massive, unbelievably huge difference. It can take up to 30 minutes just to travel 100 feet in Alien: Isolation. When every step forward is an important and dangerous one, progress markers are vital. Dying could scrap an hour of gameplay if you weren’t thorough or took a route that didn’t include a save point.

And — as you may have figured out — dying is something you do quite often in Alien: Isolation.

The aftermath

After three hours with Alien: Isolation, I made very little progress. I couldn’t quite get the hang of it — even on the easy difficulty.

I am not shocked that I suck at it. I knew that was going to happen.

However, I was surprised that I didn’t enjoy my experience. Somewhere in the haze of constant impalement, Alien: Isolation stopped being scary. The first dozen or so times the alien sliced me up, I jumped, laughed at myself, and carried on.

But you can only endure so many horrible deaths. After a while, these are frustrating — not scary. I noticed that myself and many of the other writers weren’t yelling out of terror; we were yelling because we were angry. This game was not keeping me on the edge of my seat; it was pissing me off.

Alien: Isolation has a striking look and feel to it and definitely features an near-omnipotent bad guy, one of the strongest I’ve gone up against. Playing it is quite a unique experience.

However, I didn’t have fun playing Isolation. Maybe I am just too set in my ways, and these freaky new features are too much for my fragile gamer brain to handle. Maybe Isolation is meant to illicit a more serious response from players, and my frustrations are meant to mirror the frustrations of someone trying to survive an impossible situation.

Still, I can’t help but think that games should be fun, and I think Alien: Isolation’s harsh practices will steer it away from that for most people.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More