GamesBeat: And you’ve learned what?

Lanning: What you learn is that if you involve the audience earlier, if you share with them and take in their feedback, they’re not looking for the perfect end product. They’re looking for companies they can engage with and believe in. They’re looking for a product that they like and they can feel closer to. They don’t need it delivered to them on the platinum platter. They want to feel as though they’ve been involved in its creation along the way.

That was a big wake-up call for me, because I was more cynical. I thought people did want that perfect tent-pole product, and if it wasn’t that, they’d rip you apart. When you’re playing in the triple-A retail space, they do.

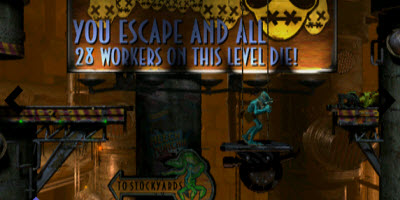

Then we started polling them. Overnight, we had thousands of results back. We’d get surprises. The reason we’re making the game we’re making now is, with this dialogue and this discussion with our audience, we find that they would be very happy if we did something like that. Yes, they would like us to make a big new title with a big new story and fresh new characters, but if we aren’t able to do that, they would like us to revisit some of the old things and do them better, add new 21st-century dimensions to them. That’s what brought about New ‘n’ Tasty.

GamesBeat: How did you proceed?

Lanning: What’s interesting there is, the audience told us the product that they’d like to have. We then polled them again and held a sort of competition to name the title. We hired the biggest person in the fan community to manage the fan community. He’d been doing it for seven years and we weren’t even building a product. [Laughs] The mod community has been doing this for years with id, Epic, and Valve. People put out mods and the best of those mod-makers get hired. It’s a great thing, and we were never able to take advantage of it. But now, at least, through digital distribution, we’re able to connect with the audience and poll them. They are giving us back the answers that we’re looking for. Also, we’ll find out who’s creating really cool art.

It was an artist in the fan community that created these deco-style posters of every game we ever made. It was completely outside the design style of Oddworld, totally not Oddworld. It was Art Deco-ish 1930s style. We just loved them. I love when I see surprises in creations that other people are building on that I wouldn’t have thought of, that I wouldn’t have directed in that way. I really respond to that positively. It’s exciting to see that. So we hired that guy to design the new logo. He designed the New ‘n’ Tasty logo.

We always thought of Oddworld as more like a rock band, anyway. Rock bands don’t start with business plans. They just want to make cool stuff that they believe in. We were always more in that camp than having an intelligent exit strategy and all that. In embracing the community, this title was able to be shaped by the audience, to be named by the audience, to be branded by the audience, to be illustrated by the audience.

I even found this girl—She contacted me saying, “I want to do music for your games! I love your games! I had the Christmas cards when I was a little kid.” Her name is Elodie Adams, out of Australia. This voice is incredible. It was giving me chills. I would love to see that some of these people, through helping us, get more exposure on their own. In the indie model, it’s very easy to say, “Hey, we weren’t planning on licensing a song for our credits. We don’t really have anything in the budget. We’ll get you something. But we’d love to host links to whatever you’re selling.”

GamesBeat: How did all this lead you to the PS4 as opposed to Microsoft?

Lanning: Sorry. Didn’t mean to belabor that point. The PS4 was really a surprise. I think what led to that was, Sony did something incredible that we didn’t see coming. They created, on PS3 and PSN, backwards compatibility with PS1 titles. A number of people from back when we launched the original Abe game are still at Sony. Abe had a lot of support from Sony. We were never a first party, although often we were associated with them that way. They didn’t pay us anything. We were a third-party. But they were supportive because they had a culture of people who liked games and liked our game. A lot of those people continued to grow in the company.

As PSN became available, we started to realize, “Hey, we could put the Abe games up here.” We already had them on Steam, but it never occurred to me that we could do that. New hardware is always resistant to backwards compatibility because they want to show new software, show off those new chips. They don’t want the old library. That’s kind of like CD companies saying, “If it was on vinyl, we don’t want it on CD.” It’s kind of a catch-22 of chip-maximizing sensibilities. The audience, on the other hand, wants the biggest library with lots of choices. The music industry is the prime example of that. Just because a new piece of delivery technology comes out does not mean people don’t want to hear Elvis on all of that. The game industry was saying, “Sorry, no Elvis on our new CDs.”

That was a dilemma that I feel the industry had suffered through for many years with the console wars. We can go into the reasoning, but I still feel like the industry suffered because of it. It blew me away that PlayStation had started looking at it more like the way Apple handles the iTunes store, where it’s really about the music. Sony seemed to be saying, “It’s really about the games.”

GamesBeat: How does the new download business work?

Lanning: Well, we’re already on PC. The game had released on PC and PS1. For us, we’re self-investing. We placed the bet to not sell the company in 2005 and to not continue taking what I call “bad money.” Bad money was, like, Stranger money, where you’re going to do a lot more work for a lot less reward and a lot higher risk. This is not why we were creating games. We were just trying to figure out, “How can we afford to take what we do have, self-finance it onto various platforms, and get there?”

Steam was the first. Then we got onto other PC networks like GOG and some others around the world. But with the PSN, when we got our games up there, we didn’t have to really invest. Our games were already compatible. We were able to take our existing library and basically put it there. Then the sales from that allowed us to start to invest. Let’s convert Munch and Stranger and get them on the PSN. Let’s get them on PC, on Steam and GOG. Being out there, a $10 product was now returning $7 back to us. When we released those games at $60, let’s say we had a 20 percent royalty. After we earned back our entire development budget – when that 20 percent paid back all of the expenses – if that game was still $60 on the shelf, which it wouldn’t be, we would get that same $7 a unit.

This Christmas I was shocked to see it, but we were number one in the U.K. and Europe on Vita. That lasted for a few months. In the U.S. we were number two. That’s a game built in 2005.

GamesBeat: This let you make a comeback?

Lanning: What this micro-budgeting, self-financed approach also allowed us to do is look at each opportunity and care more about the people who would be engaged in the game, rather than how many units we could sell on the platform. When we built the Vita version, it was all about trying to make it as natively friendly as possible, taking advantage of what makes the Vita great. If we were at a big publisher, we wouldn’t have been able to do that. They would have said, “It’s not that many sales. It’s a small installed base. We shouldn’t be spending this much time and money on it.”

As a small group, we’re able to say, “We don’t know how big Vita is going to get, but we know that the people who bought those systems now are pretty passionate about it and they want great games that play great on those systems. So why don’t we do as well as we can to make it play as well as we can for gamers?” Not for investors, for gamers. If we do that, we think gamers will respond, and they did. It wasn’t like we were selling millions of units, because there wasn’t an installed base that big to sell to, but we were able to be in the charts again with very small budgets and a lot of passion.

All that led to the point where we could say, “We still can’t afford a $10 million product ourselves, but what can we do?”

I felt like we had a dilemma. We were exhausting the library, but we hadn’t made enough money to start financing those big titles.