We’ve all heard the predictions: Digital distribution is the future of gaming. Not only do all three major home consoles offer downloadable titles via their online stores, including past games that were once only available on physical media, the PSPGo will soon hit the streets without a slot for a cartridge or a disc.

We’ve all heard the predictions: Digital distribution is the future of gaming. Not only do all three major home consoles offer downloadable titles via their online stores, including past games that were once only available on physical media, the PSPGo will soon hit the streets without a slot for a cartridge or a disc.

Meanwhile, Steam and a dozen services just like it are delivering games, new and old, to eager PC customers, further decreasing the ever-shrinking PC game share of retail shelf space. There’s even OnLive, the magical “cloud” gaming device that threatens to eliminate all consoles and graphics cards in the ethereal future.

The naysayers question the penetration of broadband Internet and point to the nebulous issues that digital rights management and end-user license agreements will bring in the all-digital age, but I offer a simpler counterpoint:

Super Potato.

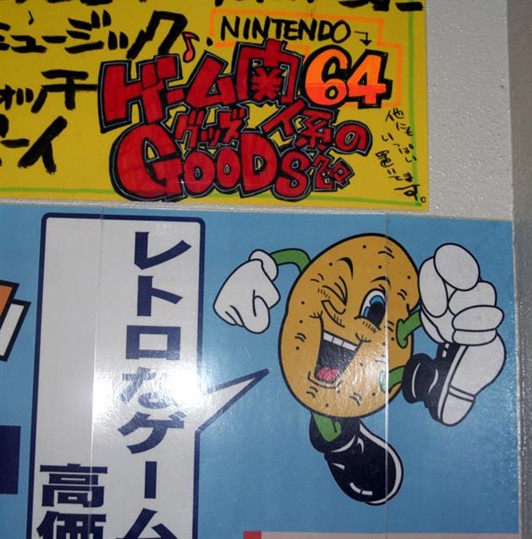

For those unaware, Super Potato is a videogame store in Japan. There’s more than one outlet but it’s not a chain on par with Softmap or Yodobashi Camera.

The shop I frequent is located at the outskirts of Osaka’s Den Den Town and is sandwiched in between two similar-looking stores. Aside from the silly name it’s quite easy for the uninitiated to take one look at it and decide it’s just another game store before walking off to the nearby subway station.

Certainly, the first floor offers nothing out of the ordinary; their display of Wii and DS games spills out of the shop and onto the sidewalk because those are the hot properties in Japan right now. Even if you step inside, you’ll be greeted by the usual Japanese videogame retail environment.

The narrow shelves are packed with games (new and used) and there’s the din of non-stop advertising, both from full-size TVs and from mini-monitors on the shelves themselves. There’s not enough room to bend over to look at the bottom shelves, but if you’re quick you can squat down and stand back up before someone accidentally steps on your hand.

It is on the second floor of Super Potato where all the magic is kept. Just climbing a few steps is enough to drown out the aggressive noise of the first floor with the charming tones of the 8-bit Famicom.

There’s a TV in the stairwell that runs a (seemingly) never-ending countdown of classic Nintendo games. Whether these are best-sellers, fan favorites or simply a random, nostalgia-driven assortment, I couldn’t say because I’ve never asked.

What I do know is that I always linger on those stairs to see what’s “playing.” It doesn’t matter if it’s a game I remember or one I’ve never heard of, because I am entertained either way.

The top of the stairs might as well be a time machine, because the entire floor is dedicated to retro gaming. The layout is similar to the floor below: there’s still lots of TV screens and impossibly cramped conditions, but while the first floor is a cacophony the atmosphere of the second floor couldn’t be more inviting.

For starters, the shift from plastic and metal shelves to wooden panels is much warmer and soothing to the eyes. Likewise, the TVs don’t show advertisements for games, they just show games. Some you can play, others are just demos, but both serve as a more honest and direct representation of gaming than any commercial.

And then there’s the games: thousands and thousands of games. There’s a rainbow-colored assortment of Famicom games on one shelf and stark-white rows of PlayStation games on another.

Grey Super Famicom cartridges, golden Sega Saturn CD cases, massive black Neo Geo ROM carts, every console of the past twenty-five years has a shelf to call its own. I remember once seeing an entire arcade joystick board for sale, ripped from its cabinet and modified to work on a home console. I would have been tempted to buy it if it hadn’t been larger than my dining room table.

For me, the main attraction is actually the “shelf of dreams” as I call it: all the consoles one needs to play the games in the store, individually shrink wrapped (or occasionally in the box) and stacked to the ceiling.

I stare at it and think of all the birthdays, holidays and special occasions that these devices represented. I spent months saving my allowance whenever I wanted to buy a new console. Now I can look at this shelf and, with whatever cash I’ve got on me, walk out the door with at least five or six different machines. If I were to hit the ATM first, I could probably buy enough software for three entire childhoods of memories.

In short, Super Potato is love. There are plenty of retro game stores in Japan and at least ten of them are on the same street in Den Den Town, but none of them will tug at your heart, reach into your brain and ignite your passion for videogames like Super Potato can.

I’m no longer into collecting but I still go out of my way to visit Super Potato every few months to bask in its warmth and live vicariously through its stockpile of nostalgia. I can go into an arcade and entertain myself by watching the attract modes and other players, but I can put a huge smile on my face just from staring at all the plastic sitting on Super Potato’s shelves.

Which brings me to my original point: in a digital distribution retail environment, there won’t be a Super Potato. Sure, the Wii and the PlayStation 3 will eventually be stacked on their obsolete console shelf alongside purple Gamecubes and Virtual Boys, but no one’s ever going to be reminded of the summer of 2008 by looking at copies of Braid or Mega Man 9. If (when?) discs are ever completely eliminated from the videogame market, then the products we love will never be enshrined in any dedicated store like this.

While I admit the online store model is a hell of a lot more organized and convenient for people like me who deplore the tediousness of handling all these discs and boxes, there’s no emotional value to be found by pressing “browse by title.”

A great example is Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, a game so beloved it can be found on both the PSN and Xbox LIVE as well as hidden inside Castlevania: The Dracula X Chronicles on PSP.

I’ve clicked past it on the list of PSOne titles dozens of times without ever putting it in my shopping cart. But when I saw it among used PlayStation games here in Japan, I felt the memories flood my mind and I ended up buying it at twice the cost of PSN if only to play it in Japanese for a change.

Another example is Doom. Thanks to an insane New Year’s sale on Steam, I bought the original and its sequel for ninety-nine cents apiece. I’ve barely touched them in the months since, but how could I resist such a deal?

I’ve spent more than ninety-nine cents on novelty flavored Pepsi, so two of the great PC games of my teenage years was a no-brainer. However, I can promise you that seeing those titles on my list of installed games doesn’t have a fraction of the impact that picking it up in my hands does.

Whenever I see a used PlayStation version, I immediately recall the night my friends and I gathered all our resources and rented a copy of the game so we could have two PlayStations running on two televisions in order to play co-op mode. It was only one night but I’ll never forget the sheer giddiness of the experience as I cackled at seeing my friend’s space marine run across my screen.

I am a realist as well as an optimist. I think buying games online and having them “delivered” instantly to my hard drive is a wonderful thing. I resent juggling Blu-ray discs every time I want to watch a movie because I keep BioShock ready to go in my PS3 at all times, so the ease at which I can go from PixelJunk Eden to PixelJunk Monsters is very convenient.

Yet the prospect of an all-digital (or all-streaming) future is a bleak one to me because I’ll miss the colorful charm of Super Potato, where the games all cost money but the memories are free.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More