The following contains spoilers for Journey

Journey is to be applauded for several reasons. It is a graphical marvel, both technically and artistically delivering with its looks. It tells a moving story without the need for protracted cutscenes, or dialog of any kind.. With its unique anonymous multiplayer, it creates a scenario where a stranger entering your game is not only bearable but preferable to being alone. It, while perhaps not a great videogame in the traditional sense (remove combat and fail states and there will inevitably be detractors and defenders yelling 'It's boring!' and 'You just don't get it!'to each other across the electronic abyss) is a phenomenal experience that everyone equipped with a PS3 must have. A Journey everyone serious about games as a hobby must make (I know, but at least I didn't make the tired lyrical reference).

Journey now joins the likes of Team ICO's efforts as being goto titles to reach for when people talk about videogames as a medium not saying something or making the player feel.In playing Journey though, I couldn't help but think of the inaugural member of gaming's art house, a 28 year old classic oft forgotten that shares a lot with Thatgamecompany's latest.

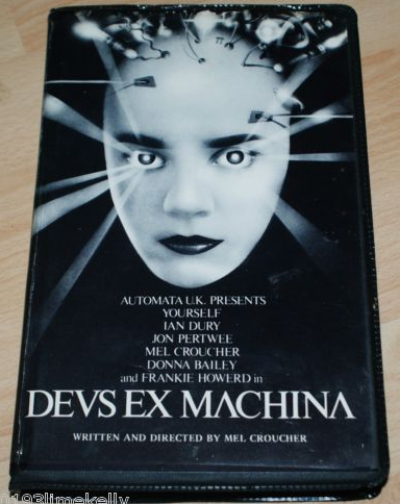

Deus Ex Machina was released on the C64 and Spectrum in 1984. Developed by legendary British writer and developer Mel Croucher, it broke ground not just by being considerably more high concept than its contemporaries, but by having a large number of celebrities involved with the project. New Wave musician Ian Durie, comedian Frankie Howerd and actor John Pertwee joined Croucher himself in lending their voice acting and musical talents to the game.

Deus Ex Machina was released on the C64 and Spectrum in 1984. Developed by legendary British writer and developer Mel Croucher, it broke ground not just by being considerably more high concept than its contemporaries, but by having a large number of celebrities involved with the project. New Wave musician Ian Durie, comedian Frankie Howerd and actor John Pertwee joined Croucher himself in lending their voice acting and musical talents to the game.

Voice acting in a 1984 videogame seems impossible, but it was a reality thanks to some clever sideways thinking. DEM shipped with two cassettes- one containing the game itself, and one the soundtrack tape. Once the game loaded up, the player had to switch tapes and hit play at the right time for the soundtrack to sync up perfectly with the gameplay. This innovation eventually wound up hurting the game however- shop stores found the two cassette case DEM came in didn't stack well on the shelf next to the other games and many refused to stock it, lending the game a rarity that with its uniqueness would assure its cult status.

Production values and forward thinking aside, it's easy to think that Journey and Deus Ex Machina have little in common after all. DEM was a 'talkie' game with celebrity voice overs long before its time, but Journey takes a much different approach to story delivery. That story the two deliver, meanwhile, is what I feel links the two.

Deus Ex Machina is set in a not too distant dystopian future with test tube children born into the 'machine'. A defect leads to the birth of an 'accident' which the player then controls. It's a fairly dark set up in contrast to Journey's wide eyed vastness, but both lead the games into following the seven stages of man from Shakespeare's As You Like It.

All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances;

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His acts being seven ages. As, first the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse's arms.

Journey starts bewilderingly, with your character sitting in the dust. Initial button presses fail to do much until one of the very few pieces of tutorialisation appear- a diagram prompting you to tilt the controller (or move the sticks if you must (as did I)). Unable to jump until fist collecting scarf fabric, tumbling over sand dunes is undeniably child like.

And then the whining school-boy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school.

And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress' eyebrow.

Moving from what you only find out afterwards is a cleverly designed level select hub into the bridge building section, you are taught like the schoolchild the mechanics of the game- issuing sonar pulses to weathered fabric in order to bring life to the environment. It is here you meet your companion, another bewildered youngster in the world. Your sole means of communication that director Jenova Chen himself has described as 'singing', either embraced and evolved into flirty chirps by your partner or shunned, seem to match Shakespeare's 'woeful ballad' perfectly.

Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon's mouth.

Journey lacks combat, but not conflict. The flying snake like monster that appears halfway through the game is terrifying in its Shadow of the Colossus esque size. Although the player didn't pick this quarrel, the soldier's fear in the cannon's mouth matches the fear I certainly felt when spotted by the beast. Although there's no failing out or dying in Journey until its time is done, losing your scarf, and the joyful flight it brings when struck, hurts and frustrates.

And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part.

Toward the end of the game, Journey feels at its most conventional and game like. Sure, sand skiing through gates is a very videogame like activity earlier on, and you can argue escaping from the snake monster requires stealth techniques honed by games over the years, but working your way up a central pillar to a doorway up high requires a repetition we are all trained for. Jump up, hit a switch by illuminating wall paintings. Progress higher and do the same. And again, and again. This isn't a complaint in the least but it's an important note to make because it suits the justice analogy so well, and I'd be surprised if the placing of this section was not deliberate. At this stage you feel learned and world wise as the player.

The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slipper'd pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side,

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank; and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound.

It's a challenge not to be moved by Journey's push through the snow. The vibrant fabric cloths in the scenery are now frozen, the sonar chirps are diminished, and the only way to bring colour to your own character is to huddle together with your anonymous companion for warmth. As movement is crippled, what you suspected from the start is confirmed- this is a Journey through life itself. Both players finally collapsing together is rivaled by Deus Ex Machina's own ending- a frantic and futile battle to bust blood clots in a failing heart- for its emotional effectiveness.

[embed:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k7n5zeN6d7E&feature=related ]

Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

Yes, Journey seems to take the same Shakespearean path that Deus Ex Machina did all these years before.Where Croucher's oblivion, however is in wry British dark humour- 'Imagine all of this is but an electronic game. Your life is represented by a percentage score' – Journey's final section is a glorious burst of colour and kinetic energy, before ending sans corporeal form.

All of life's a stage, or all of life's a game, or all of this is a bit too pretentious? I don't know, but the fact that Journey inspires these thoughts, just like Deus Ex Machina, says a lot about gaming as a viable art form, and that's a great thing.