[I am a student of Stony Brook University, the institution at the center of this article. This was originally written for a journalism class and the tone is a bit more mainstream media than enthusiast press. Nonetheless, I think it's an interesting article, particularly once it gets into the obstacles facing the preservation of modern games, and so I figured I'd share it.]

The oldest book in the Special Collections at Stony Brook University is an illustrated history of the world called “The Nuremberg Chronicle.” Printed in 1493, little more than 50 years after the invention of the printing press, it contains some of the first examples of printed illustrations.

This relic of the print age now resides alongside the William A. Higinbotham Game Studies Collection, a collection of video game cartridges, consoles, book and magazines spanning 20 years of video game history.

The collection, opened in the fall of 2011, joins the growing group of museums, libraries and universities around the United States that have begun to preserve video games and the culture surrounding them.

Similar projects exist at Stanford University, the University of Texas at Austin, the University of Illinois and the University of Maryland. Even the federal government has participated. The Library of Congress helped to fund the Preserving Virtual Worlds project, which sought to define preservation standards, an issue that is still debated.

Henry Lowood, head of the How They Got Game preservation project at Stanford University, equates video games to books or films as cultural artifacts that need to be preserved. More important than preserving the physical media of games, he said, is documenting their culture.

“They’re becoming a very important part of our contemporary culture,” he said, “and if we don’t have an ability in the future to look at the history of digital games as a medium and the history around them, we really will have an incomplete picture of the culture of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.”

Building the Collection

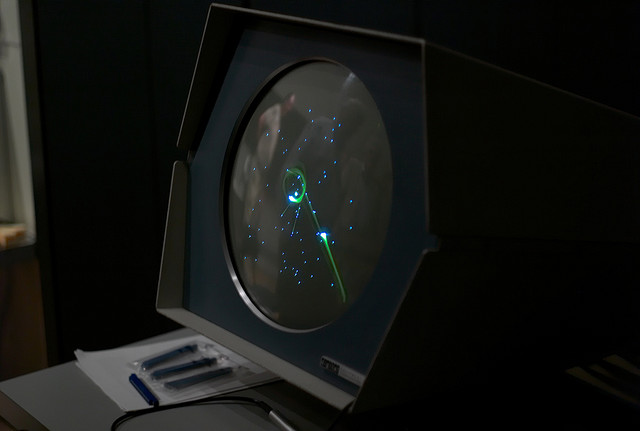

Stony Brook’s collection takes its name from William A. Higinbotham, a Brookhaven National Laboratories scientist who created “Tennis For Two.” While scholars continue to debate its status as a video game, the tennis simulation, built from lab equipment in 1958, is often credited as the first electronic game to use a graphical display and dedicated controllers, video gaming’s own “Nuremberg Chronicle.”

The process of building the collection began in 2008, when Raiford Guins, a professor of digital cultural studies at Stony Brook, contacted Kristen Nyitray, the head of Special Collections and University Archives.

“We started to talk about how we could document the history of video and computer games, but also talking long term about the preservation aspect of it,” Nyitray said. “I think that’s where we really connected.”

They outlined a plan to create a four-part collection: a game laboratory open to the students of computer science and game-studies classes at Stony Brook, a circulating collection of game-related books, a special collection housing even more games, consoles, rare books and magazines, and a website to serve as a hub for the whole thing.

Guins, who declined to be interviewed, provided the earliest materials from his personal collection and donations from colleagues. The collection now includes approximately 700 games published between 1977 and 1999 and more than 2000 magazines.

Because of financial restrictions, however, the focus of the collection is now on expanding its print offerings. All games and consoles in the collection have been donated, Nyitray said, and they currently have the funds to pursue only books and magazines.

“The library doesn’t have the funds now to do more than buy books,” said Darren Chase, the Stony Brook University Libraries’ subject specialist for game-studies, “but there are plans to, hopefully in the next couple years, expand the Higinbotham Collection and to expand access of students to gaming platforms beyond just game-studies students.”

The Authentic Experience

Collecting, storing and maintaining the physical embodiment of games — the metal and plastic of cartridges, floppy disks and CDs — is an expensive prospect. One of the Higinbotham Collection’s goals is to preserve these games and consoles in an effort to reproduce the original experience of playing games. Its game lab, where students can sit down and play the games, even uses old CRT TVs, instead of modern flat-screen TVs, to maintain the original look of its games.

According to Henry Lowood, a video game archivist at Stanford University, this model of preservation is important for the study of games and their creation but is ultimately limited by the passage of time.

Vintage video game consoles are no longer in production and the number on the market will only continue to shrink.

“If you have an Atari 2600 and you want to start a museum around it and it breaks today, you can get another, that’s no problem, and that will probably be true for decades,” Lowood said. “But at some point, it won’t be true.”

He points to the example of “Spacewar!” another one of the first digital computer games. Developed approximately 50 years ago at MIT, there is currently only one place where it can be played in its original form: the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif.

However, the plastic and metal of a video game’s body is just a shell, and the key to preservation, according to Lowood, lies in yanking out a game’s soul — the actual computer code that gives it life.

Migration: "The Way to Go"

There are two major forms of video game preservation besides hardware preservation: migration and emulation.

Migration is the movement of the game from one physical medium, like a cartridge or floppy disk, to another, such as a computer hard drive. It creates a new place for the data to live, removing the possibility of loss due to damage or obsolescence of its original home. At that point work needs to be done to make sure the data can be installed and run on a modern platform, like a computer. This can be done through a process called porting, in which programmers edit the code of the original data to make it playable on a modern computer.

Emulation involves creating a computer program that simulates the way an old computer works, allowing migrated data to be played without having to dive in and change it.

“I think it’s pretty clear that most digital preservationists you talk to will say that migration is the way to go,” Lowood said. “I don’t think there are very many adherents, outside of museums, for hardware preservation, and emulation is seen now as something that goes hand-in-hand with migration.”

Migration and emulation, however, require computer programmers to go hands-on with code, and besides being time-consuming and costly, these methods require changing the original data.

Intricacies in the way computer systems work make it nearly impossible to perfectly replicate a game in a new environment. Even when modern video games go from a PlayStation 3 to an Xbox 360, for example, the way those two systems run the data and create graphics is different, and the game data need to be modified to work.

Preservationists need to decide, Lowood said, which changes are acceptable and which are not.

“What falls in the not acceptable category would most likely be changes that alter the experience of the game in some way,” he said, “changes that affect the game mechanics or significantly change the look and feel of a game so that you really don’t feel like you’re playing the same game any more.”

Nyitray has no plans to expand the Higinbotham Collection into migration and emulation.

“We’re going to try to keep our hardware in workable condition,” she said, “but we’re going to leave the code-work to other universities.”

Problems Ahead

While the problem of preserving these sometimes more than 30-year-old games seems to have been solved by modern technology, ensuring that contemporary games receive the same treatment is proving to be more difficult.

Video games are increasingly moving to a download-only format, forgoing DVDs and cartridges altogether and becoming available strictly from the web as files downloaded to an Xbox, computer or smartphone. Because of the strict ownership rules set in place by the various digital-only retail services, such as Valve Corporation’s Steam for computer games and Microsoft’s Xbox Live Arcade on the Xbox 360, preservationists have very few legal options when it comes to duplicating and distributing modern games for research purposes.

Download-only distribution, copyright law and end-user license agreements – those lengthy contracts users agree to but seldom read when installing a new computer program – are the biggest hurdles facing video game preservation at the moment, Lowood said.

“We as a library don’t have a legal right to just grab all that content from Steam,” he said. “The problem with these forms of distribution and the legal situation, at least in the United States, means that it’s next to impossible at the moment to think about archiving a lot of these games. That’s kind of the big elephant in the room for preservationists.”

Games played in a web browser also present a problem. Facebook games, like Zynga’s Farmville, are an important development in the way video games are designed, shared and played, but preservationists have no idea how to archive these kinds of titles that live only on servers and can have their content modified daily.

“We don’t have a stable artifact like we do with a boxed game,” he said. “It becomes pretty difficult to define what exactly the game is.”

The solution lies in the hands of game developers and publishers – the copyright holders. They need to start thinking about their games as historical artifacts and working with preservationists to document them, Lowood said. Otherwise, preservationists will need to continue to skirt copyright law for what they see as the greater good.

“Sometimes people in this area just have to do something,” he said, “and, hopefully, you can ask for forgiveness later.”