The games industry is slowly emerging from its annual summer chrysalis like a butterfly with a severe vitamin D deficiency. As the heavy hitters of Rage and Batman Arkham City take their place on store shelves though, what's prompted me to awaken from a real life stuff enforced blogging hibernation of the last couple of months is the early autumn emergence of three remakes.

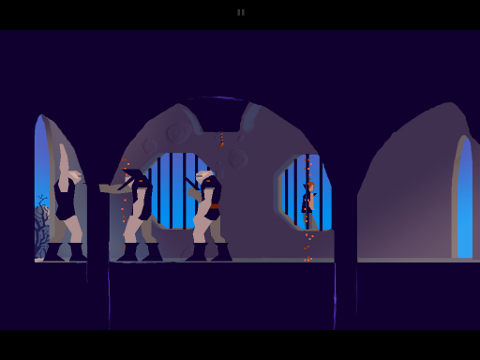

Eric Chahi's 1991 Amiga cult classic Another World, while not a masterpiece of a game (more on that later) is an important title. Telling the story of a scientist teleported onto a hostile alien planet with an unnamed companion his only ally, Chahi's game does without a HUD and dialog of any kind, relaying its story almost entirely in gameplay. As you escape from a prison cell, you pass other aliens loitering in cells. Heading through caves and back above surface, the bustle of sprinting guards and sizzling laser fire gives the impression of an oppressed people rising up and rioting against their government. Your relationship with your alien friend is developed through animation touches and slight audio grunts rather than ten minute pieces of exposition. Only occasional musical interludes add to the atmosphere of being a stranger in a very strange land, along with a strong sense of place that's remarkable for the time- blasting a rock allowing water to fill a cavern is fine enough as a solution to a puzzle early on, but returning to the same area later, this time having to swim through, is vital in making the environments feel real.

All this is great. It's just that Another World is not a good game. Purely scripted by necessity, this here is a memory test first and foremost- a struggle of trial and error, where attempts and deaths in their scores distend the title's twenty five minute length. With a lack of save points and limited lives, its hard to imagine anyone having finished the original. Now the 20th anniversary edition of the game is available on iOS devices though, perhaps more people will see the title through to its underwhelming conclusion (spoiler alert: its increasingly sci fi epic like feeling is blown in the last five seconds, where, stuck, for an ending, Chahi seems to just go 'aw screw it, just have them escape on a dragon or something'). While many will insist on poo pooing touch controls for such a game, its intuitive setup of taps and swipes actually does an arguably better job of the wide variety of moves at your disposal than the one button joysticks of the age ever did.

No, what will slow your progress here is the weakness of your character. He walks at a snail's pace, lurches into an ungainly run, kicks feebly at shins and leeches and jumps gingerly into gaping maws. There is no doubt in my mind that this is intentional design choice- you are after all playing an unathletic, albeit wealthy Ferrari driving scientist. Obviously combat skills will not come natural to him and running and leaping will not be something he's used to. Yet hamstringing the player adds to the scripted nature of the game to the point where the only way to completion is to remember why you died and use this foreknowledge to avoid peril on restart- skill is not a factor, which is why, while I appreciate the things Another World did, it frustrates much more than it delights.

The themes of isolation and companionship are familiar to Team Ico fans, who saw Ico and Shadow of (aka Wander and) the Colossus re-released on PS3 recently. Playing Ico and Another World in tandem makes the similarities between the two especially apparent. Like Chahi's game, Ico had a hugely strong sense of place with its fantastically designed castle ten years later. The story beat of a relationship budding despite the lack of verbal communication is the same, and even Ico's shadow beast enemies bring to mind Another World's imposing black beasts.

But Ico, too has a tendency to handicap the player. The eponymous horned child is squirrely to control, darting this way and that at a moment's notice and swinging weapons wildly. For the most part this adds to the sense of character, but in the one or two instances where precision and timing are of importance, that grand sense of place is forgotten, and instead controllers are flung. Rather than enhancing it, Ico's jerky motions can shatter the illusion.

Character control is also a criticism levied at Shadow of the Colossus, Ico's double pack partner. In a game where physical struggle against a mammoth living creature takes centre stage though, it's hard to argue with the decision to make Wanda fall short of an expert climber. Perhaps though, Shadow detractors have more of an issue with early pacing- coming back to the game on PS3, I had forgotten how tyough it was to scale the first colossus, all to easily being rebuffed and having to start from scratch. Compared to the relatively easy creatures that follow immediately afterward, the feeling of being deliberately handicapped is emphasized from the get go, which is something that a lot of people resent.

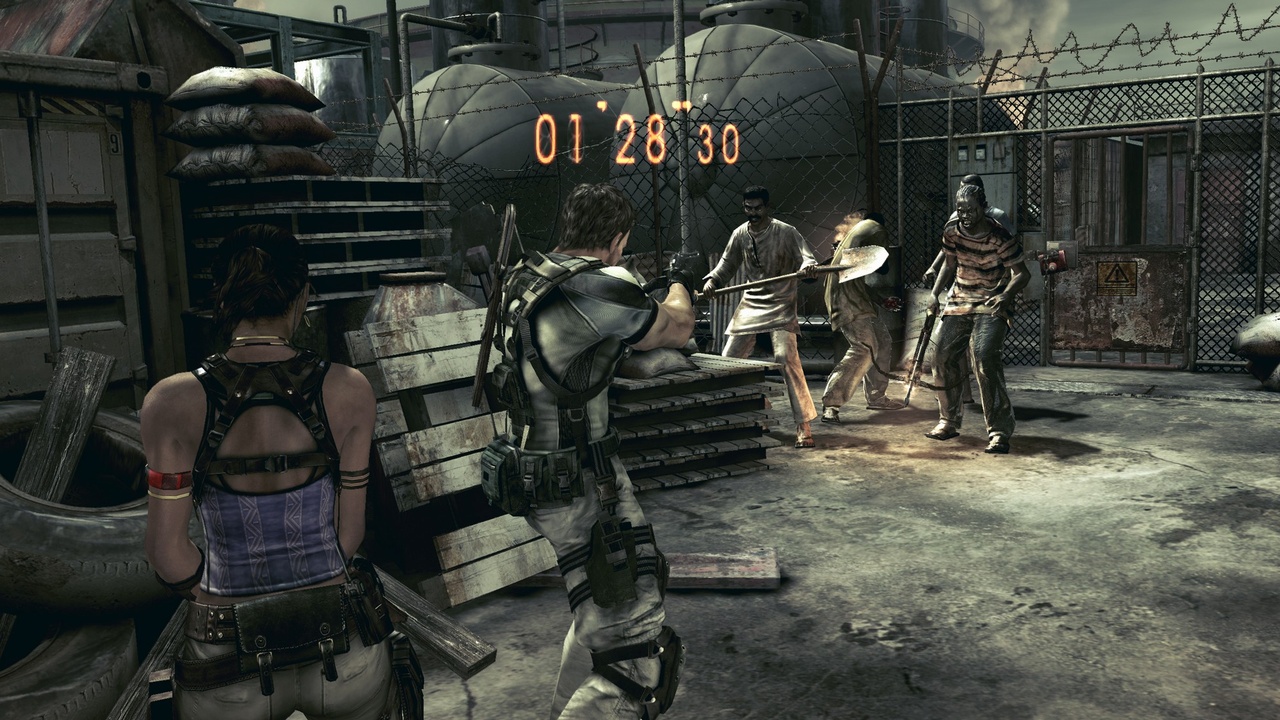

Just as I resent the Resident Evil series' consistent attempts to cut the player off at the knees. My incompatiibility with tank controls shortened my sessions with the pre- rendered original games, and the whole lack of moving and shooting was a determining factor in my giving up on 4 (as well as the fact that I was just finding the whole thing dull and brown and uninteresting- having now broken the game writing commandment of 'though shalt not criticize Resident Evil 4', I expect to be struck by lightning within the day). My fiancee though, at best an occasional gamer, fancied a pop at Resi 5, and a blast of local co-op set on easy should in theory have been fun and frustration free.

And it is, at times, fun. Frustration though, even on easy, comes in spades, not because of the gameplay itself, but the most inane inventory system of all time which through its pressing of triangle and highlighting and clicking circle and scrolling to give then confirming and 'no don't pick THAT up, that's for MY gun' and 'bloody hell come here round the corner and let's figure this out' manages to convey less of a George Romero feeling as it does of that episode of the Fast Show in which a skit involving figuring out a bar tab is played out over the course of an entire thirty minutes.

[embed:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y6QgHUJIQ5Q ]

The defence of course, is that without the handicaps, Resi would struggle to frighten. Put yourself in the characters' shoes, fans say. Chased by zombies, you'd be paralysed with fear and tripping over your own feet. You'd have to stop to steady your aim, or else fire wildly. You would struggle with items, fumbling to put bullets in a gun. Yet to me, Resident Evil isn't an exercise in fear, it's in one of frustration. I know I can retrieve a book, or tasty snack from my bag when asked. I haven't fired a gun, but I imagine with the proper training, I could move and at least roughly aim at the same time. Like the issue of games past where characters are stopped in their tracks by waist high walls, I don't feel more for my characters plight when I'm hamstrung like this. I feel neither empathy nor a deeper sense of immersion. I feel let down and pissed off.

Perhaps there is a case to be made for sacrificing usability in order to increase challenge. Bar the occasional issue in Ico, and the first battle in Colossus, those games almost work out perfectly. Heavy Rain, a mess of a story, was affecting and memorable in moments when characters were under severe duress, and quick time style button prompts and combinations became more finicky and easily missed. I'll let you sound off in the comments below to add opinions.

In the meantime, how about this for a concept- rather than an adventure/RPG where character classes have differing special abilities that compliment each other, how about one where one player in a party is blind, or deaf, or has difficulty walking? A game where players work co-operatively to overcome adversity rather than squashing challenges underfoot? Rather than sacrificing the usability of game controls for the supposed sake of immersion, let's take designing disabilities a little more seriously- we might learn something about one another in the process.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More