Ninja Gaiden (Tecmo)

Ninja Gaiden’s cinematic ambitions are well-documented. The game’s story was a pastiche of martial art B-movie clichés: a boy ninja—too young to look as buff as he does on the box art—seeks revenge on the death of his father. Along the way, he encounters double-crosses, missed opportunities, and the discovery of a greater evil than he could have imagined linked to his father’s death. All this narrative, written not spoken, is presented through characters in slightly-animated stills with a low-tech, but evocative soundtrack, and each cut scene is preceded by a crushingly difficult and surprisingly fast-paced platform game.

[embed:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_rkaiKYEkDQ&feature=player_embedded ]

Ninja Gaiden’s opening cut scene is one of gaming’s most iconic, detailing the duel that ended the father’s life and the reading of his last letter by his son. The action/cinema dynamic offered players motivation beyond the basic fun in playing a game. This was cinema despite the low-tech circumstances and players played not to just to see what happened, but how it happened. Ninja Gaiden wasn’t the first game with plot, but working within its own limitations, it created a real sense of drama that would elude developers with larger budgets and better technology in subsequent game generations. Only in recent years have game developers seemed to reel in their resources and deliver easily-digestible, yet meaningful narrative, as in the Uncharted series. Even so, Uncharted traffics in modest familiarity, being a modernized, quick-witted Indiana Jones impression in nearly every moment. In other words, for all of its technological advancement, Uncharted still needed to scale back its ambitions as Ninja Gaiden was forced to, in order to be great.

Batman: The Video Game (Sunsoft)

[embed:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cxmxVbxL4Oc&feature=player_embedded ]

Batman: The Video Game features unrelenting pretension, more than the Tim Burton film that inspired it. The game’s title screen reveals itself with a flicker of Batman’s portrait before slowly fading him in. As the low-octave music builds, the word BATMAN appears with all the subtly of elephants in coitus, followed by the limp appearance of the game credits with epic chords pounding away. It takes 40 seconds and is followed by the game’s main opening cut scene. In hindsight, the game’s title and title screen’s needless clarity— Batman: The Video Game—reek of Mel Gibson-style over-importance (think The Passion of The Christ). In other words, Batman featured an awesome stupidity that pre-dates even Resident Evil and remains a problem in gaming today. As action games go, it’s sluggish and unoriginal. A stark delay stands between player input and action, and Batman carries weapons that put a middle-finger to his mythos: a ninja star, a non-Bat-shaped boomerang, and a gun(!).

Batman’s success was actually in its careful rendering of the game’s world. Even today, you probably won’t find another game that uses negative space as effectively. The game’s first level features an ominous “DON’T WALK” sign and shades of businesses’ names and lights in the background, signifying that, indeed, there is a city back there cloaked in the permanent night of 1940’s America. Sunsoft were also brilliant animators. The game featured believably animated water, lightning, machinery and human movement, lending Batman the moody mystique of a film noir. Later games, such as Splinter Cell and The Chronicles of Riddick: Escape from Butcher Bay, would incorporate similar elements directly into setting and game play. What Batman: The Video Game lacked in functionality, it made up for in overbearing, but evocative style that feels timeless.

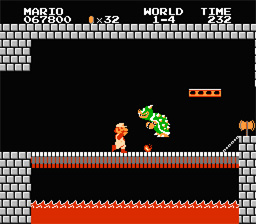

Super Mario Bros. (Nintendo)

Credit Tom Bissell for pointing out that, somewhere around 2020, the president of the United States will probably be young enough to have played Super Mario Bros. as a child. This may signify some great achievement of the hobby, but likely nothing that can be translated into legislation. It’s still important because, although video games are played by more people of all ages than ever before, the success of SMB still eclipses the success of any game today. Yes, your Half-Life’s, Halo’s, Grand Theft Auto’s, Fallouts, and Bioshocks don’t have shit on the Italian plumber from the Mushroom Kingdom.

SMB was as successful as video games got on their own merits, before Halo could build pre-release hype with Mountain Dew (despite the fact that first-person shooters bear almost no crossover appeal with non-gamers). Even with the graphical and control limits, SMB offered players something pure and universal. In this case, the players were everyone: you, your parents, your siblings, your friends. Ask any non-gamer who was alive during the time of SMB and they will recall it fondly. Just fast-forward in the following video to the 2:55 mark to see how people go crazy over the game’s pause function.

[embed:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sGQ20yDDVzQ&feature=player_embedded ]

Nintendo would make better games starring the famous plumber (Super Mario Bros. 3 was probably their best). And other iconic franchises have seen releases that are similarly bloated and ominous, but ultimately limited by genre or the fact that they’re simply video games. Gamers may love their signature franchises, but everyone loves SMB. Everyone.

—

This post, by Adam Coronado, originally ran at The Gentleman Gamer.