Picture the scene: you’re creeping through a tight, dark tunnel (probably a sewer of some kind). There’s something down here with you: you can hear it, growling, somewhere close by. You inch forward, round another corner – but there’s nothing there. You breathe a sigh of relief and turn, only to find a drooling pointy-toothed demon thing about to do you some serious misdeed.

Do you:

- Shit the bed and run.

- Alt + F4 and go to bed.

- Dispense with the pleasantries and shoot the crap out of it with your newly upgraded DemonSlayer 4000 assault rifle.

Now in most games, the obvious answer is likely to be 3. Because that’s how most games work – even the scary ones. If you have a problem, then guns are usually the solution. Games like Fear F.E.A.R F3AR are excellent examples of this school of thought. There’s loads of creeping round dinghy warehouses and a lot of jumpy moments when a creepy little girl pops out and eats your brains or whatever – but is that really scary?

It’s a particular kind of scary, beloved by schlocky Hollywood films and cheap thrillers, making heavy use of cheap camera tricks, rising pizzicato violins and musical stabs – the common or garden orchestral equivalent of a fairground ghost train. But these scary games have an intrinsic problem: making games fun traditionally relies on making the player feel powerful or capable – something that’s antithetical to the nature of fear. As the player-character protagonist you’re fundamentally capable of solving any problems you come across, scary, natural, supernatural, alien or otherwise.

Alan Wake, for example – recently released on PC – depicts a lone man battling against supernatural darkness with nothing but a revolver and a flashlight. All the ingredients are there: tense, moody music, dark and foggy woods, creepy NPCs – but somehow it’s never really that scary, because all you ever need are your flashlight and revolver. There’s always plenty of ammo to hand, and it’s never very far to the next checkpoint. It’s a good game, and it’s fun to play, but despite its best efforts it’s not really scary.

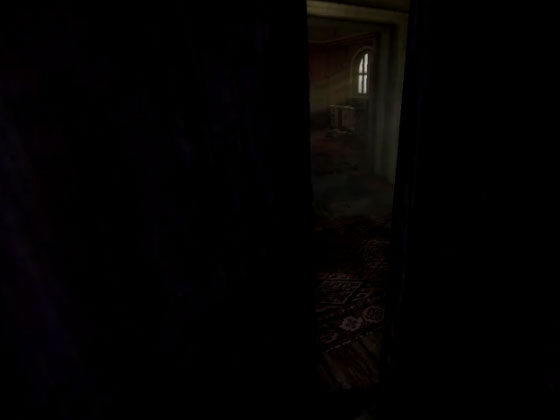

I think the scariest games – the ones that are genuinely terrifying – are not the ones where you’re fighting to save the world, but the smaller, more intimate games where you don’t get to hide behind a gun. The scariest game I’ve ever played is called Amnesia: The Dark Descent – a game in which you’re virtually helpless. When a monster comes round a corner you don’t stand and fight, because you have no weapons and no kung-fu powers to save you.

When you see something scary in Amnesia you run away and hide, often in a cupboard or behind a shelf. Then you sit and sweat as you stare at a black screen, listening tosomething banging and clattering outside. And when the noise dies down it takes a long, long time before you feel ready to open the cupboard, and peek out.

It’s not exactly the most manly of games, but that’s the point: the feeling of helplessness is what makes it so scary. I’d like to see more publishers making games like this. It’s clearly a risk, because a big reason people play games is the feeling of satisfying power (something like the recent stompy-armoured-dude sim Space Marine) but I think that defining feeling of powerlessness is, ironically, very powerful.

It does more than just make things scary. Stories are more interesting and more dramatic when there’s real peril; when all seems lost and the protagonist has the will but not the power to intervene, not when all that’s required to save the day is the ritual sacrifice of a few faceless goons. When the only tool you’ve got is a gun then every problem looks like a target. So why not try putting down the gun and coming out with your hands up for a change?

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More