When Abbie Heppe reviewed Metroid: Other M on G4TV.com, she took the game seriously as something other than pure commercial property and included some meaningful and appropriate criticism. G4’s management have scrubbed the comments section of the most egregious examples of what I’d like to point out, but fans reacted with vehemence and outright dismissal at Heppe’s commentary in a practical demonstration of the “it’s just a game” mentality.

It’s easy to feel unconcerned about the upcoming Schwarzenegger v. Entertainment Merchants Association Supreme Court case if you’re already an adult, because the ramifications of the videogame industry losing the trial might not be readily apparent. I was carded yesterday in Target buying a copy of BioShock, and they do the same thing for the purchase of DVDs that are marked as featuring violent content. If militance about checking the age of videogame purchasers is the largest, immediate ramification of the videogame industry losing this case, many of us are already dealing with that state of affairs.

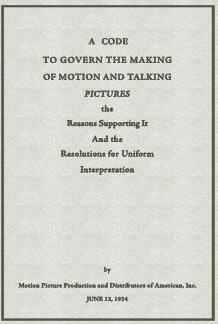

Therefore, it may seem like nothing would really change if and when other States followed suit with a law like California's, and I’ve seen enough kids who certainly looked underage buying Grand Theft Auto titles at GameStop to consider that legislation to keep them from playing games that I wouldn’t want my underage kids playing isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but in order to understand why even adult gamers may want to pay attention and care about this court case, we have to go back to the closet analogy history provides us, to wit the Motion Picture Production Code, or Hays Code, which governed the film industry for over 30 years in the early 20th century.

In their Mutual Film Corporation v. Industrial Commission of Ohio case of 1915, the United States Supreme Court ruled that movies were business, not art, and thus not covered by the First Amendment. Foreign films which didn’t adhere to the dictums of the Code were prevented from importation. Joseph Breen, the head of the Production Code Administration, actually had the authority to alter scripts and scenes in movies. Advertising campaigns for movies were held up to the same level of scrutiny.

During the days of the Hays Code, content that was risqué for the time was still produced. Filmmakers just had to be more subtle, and to a point artistic, in how they depicted that content. My concern is that videogame publishers, however, will not show the same moxy that studios did under the Hays Code, and that if Schwarzenegger v. Entertainment Merchants Association goes the wrong way we'll see all kinds of potential subject matter shunned by developers who don't want to take the financial risks of playing to a smaller audience.

Electronic Arts' recent decision to pull the label “Taliban” from the multiplayer portion of the upcoming Medal of Honor seems to validate this fear. The definitive response was written by Ian Bogost over on Gamasutra, but reducing the “enemy” in Medal of Honor to fictional combatants no different than the bad guys in Modern Warfare or Modern Warfare 2 has turned a game sold to us as a fictional depiction of a historical conflict into a fictional depiction of…well, into just plain fiction.

By moving the Medal of Honor franchise into a contemporary conflict, EA had the potential to work some serious, dramatic content into a military first person shooter, which would be unlike anything we'd seen before in the genre. It could have been a watershed moment in what we expect from military FPS titles. Instead, EA cowered from substantive discussion of the issues rather than sticking up for what the Medal of Honor franchise has always been about – honoring the soldier – and watered down thier game, ostensibly for fear of losing money.

If a major videogame publisher can't stick by the intent of an immensely successful franchise, which likely could have weathered this controversy without economic ramification, what hope is there that publishers will stand up to censorship if and when it lands on our industry in full force?

This censorship may begin with concerns over violence, but in America violence is ridiculously more permissible in our media than sex, so when violence gets censored, it’s not unreasonable to think that sex may be utterly wiped from the map of potential videogame content. From there it’s only a few short steps towards thematic censorship, and if we thought that storylines and characters were already being recycled with predictable and often tedious results, wait until the number of options available to videogame writers get truncated by censorship regulations.

When the motion picture industry got slapped with the Code, they had artists with the talent to work around those rules and still get the stories told that they wanted to tell. Other than a few luminaries in video game development, the production side of our industry seems more concerned with issues of AI, graphics and physics engines, and level design than with story and theme. I’m not convinced that we have enough storytellers available in the videogame industry to outwit censorship Codes and Boards.

Unless gamers take videogames seriously as art, no one else is going to take them seriously either, including the major publishers. Considering the ESA's defense in Schwarzenegger v. Entertainment Merchants Association depends on the argument that videogames are artistic expression and therefore covered by First Amendment protections, this is not just a theoretical question anymore.

Dennis Scimeca is a freelance writer from Boston, MA. He maintains a blog at punchingsnakes.com. If you tweet him @DennisScimeca he will get right back to you, because he's officially bored with Halo: Reach.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More