The third time may be the charm for Twitter cofounder Biz Stone. Jelly, the Q&A startup the Twitter cofounder created alongside Ben Finkel, has just opened up to the public, launching more than four months after the company announced its “un-pivot.” Now the company is one that Stone says “I’ve always wanted.” But do we really need another Q&A service?

Moving out of beta and available to all

Billed as being a search engine that taps into people’s knowledge, Jelly takes the everyday question and crowdsources the answers. Anyone can use the service, either anonymously or by creating an account. After selecting several topics they may be experts on, users may submit questions for answering, such as “Where’s the best place for brunch in New York City?” or “Where’s the best place to take a 5-year-old child?” Questions are then evaluated by Jelly’s artificial intelligence before getting farmed out to other users who have been vetted by the system as potential experts.

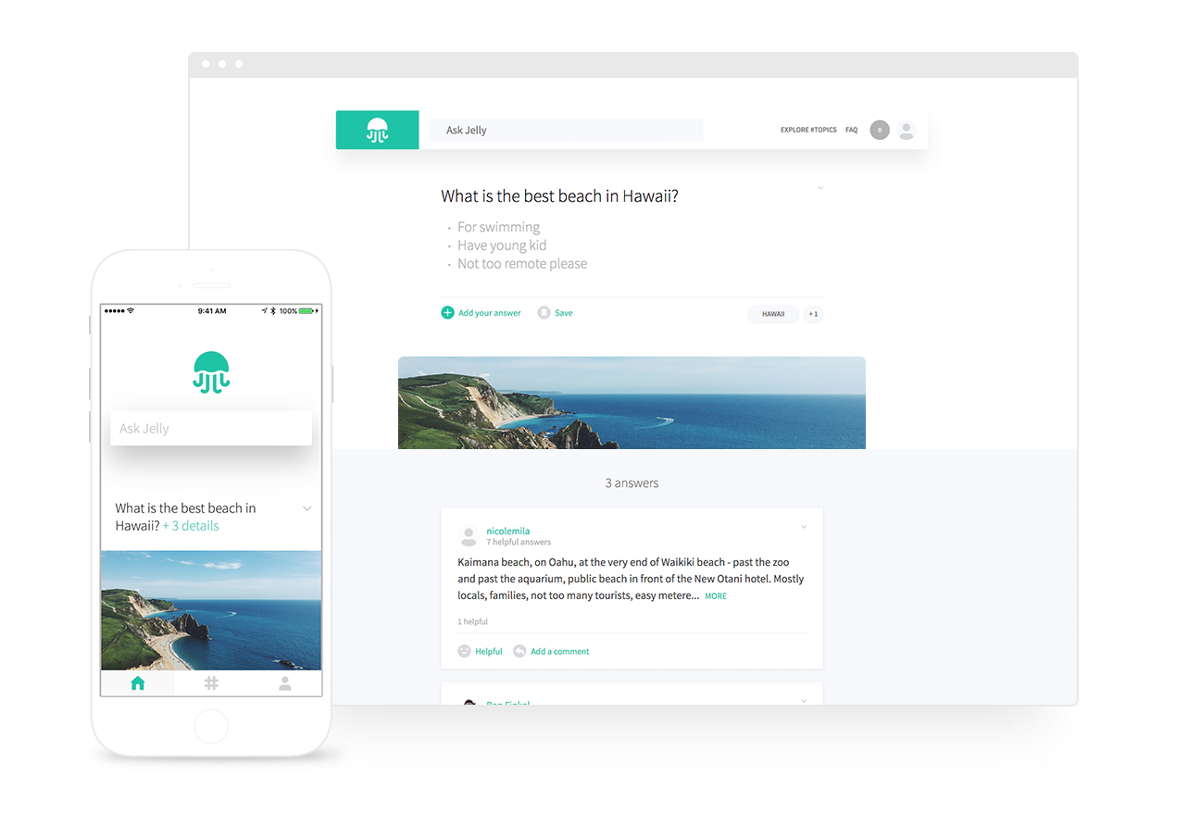

Above: Using Jelly on iOS or Web is easy and familiar. Just type into the search box.

The main feed within the Jelly app is a mix of questions and topics you’ve expressed interest in. Once in awhile you may see a random question added to the mix — but that’s not a mistake. Stone said that it’s a mechanism the system uses to double-check itself, to ensure that it’s properly fine-tuned to what’s relevant to you. All questions are shown based on topics, not your location, although future iterations of Jelly may prompt you for this information to further tailor your feed.

Stone told VentureBeat that his team built Jelly’s current incarnation in six months and has been beta-testing it for the past month with a few hundred people. However, it really took the company several years to get to this point, especially after launching its first generation app in 2014. While the Q&A premise held true, the actual execution didn’t. Stone said that version 1.0 relied heavily on using cameras and accessing people’s social networks, which didn’t resonate with users. Then the company pivoted to launch an opinion-sharing app called Super, which didn’t work out so well.

“We finally came to our senses and built this thing that we wanted to do,” Stone explained. “It’s a new kind of search engine. We’re not competing with web search, but it’s a new way to get answers to your questions.”

For the common question

While Jelly may draw some comparisons to Q&A services like Quora, it’s actually different in that not only are the inquiries of a different nature, but what Stone has in mind for the service is much bigger. In an interview, he sees what’s being asked on his service as things people “need to get through their day,” while questions on Quora and specialty Q&A sites as equivalent to Medium, where you’ll “read interesting stuff, but they’re long and involved, deep and philosophical.”

Above: Composing a question in Jelly.

Stone also envisions Jelly as growing into a platform that could be integrated into other products, perhaps something like an enterprise social network, website, or anywhere else. It’s too early for specific steps, but it’s something that the company has been thinking about. For example, a company could extract questions posted on Twitter, crowdsource answers within Jelly, and then post the response back to Twitter. “We want to be helpful, no matter where people ask questions,” Stone said. There’s also an enterprise opportunity to give coworkers the ability to ask work-related questions of one another.

Another prospect is integrating Jelly into topical sites and groups, offering its Q&A service to complement the knowledge being exchanged in these places.

Jelly features some basic artificial intelligence, which hadn’t been included on the service until the recent refocus. “This time around, there’s more science and computer science involved, all in service of finding the person to create an on-demand answer for you,” Stone said. “It may not be noticeable for you, but it’s kind of cold, hard science in finding you a warm body and someone that knows something about [the topic] — not an expert, but someone who’s been there and done that.”

Right now, this “thin layer of AI” determines whether you’ve actually asked a question. If not, Stone explained, Jelly will ask you to rephrase it to help people understand what you want or to browse through the topics. When a question is submitted, it’ll be categorized and routed to people the service has indexed as likely experts in that field. The more you use Jelly and how often you answer questions factors into the algorithm that determines how much of an expert you are and what topics you might know about. Eventually, it’ll send you questions you may not know you know the answers to, Stone said.

Jelly is still in its infancy, and there are more features that Stone’s team should be adding in. He admitted that the service has no way of managing duplicate questions, meaning that if multiple people asked “Is the sky blue?”, Jelly treats each instance as a new question. Over time, the app may surface responses from previously asked questions to streamline the experience.

Above: Jelly cofounders Ben Finkel (left) and Biz Stone (right).

The company may also implement smart suggestions to help you compose questions. Currently, you can enter your question along with some additional lines of details, but it’s a free-form text box. Stone posited that Jelly may have smart suggestions to prompt you for elements like “What’s your budget?”, “Is there a specific location?”, or “Do you have a preferred brand?”

Naturally, as with any forum-like service, one must ask about safety and privacy. Jelly does have the “basic stuff” in place, such as being able to flag a post and question, and we’re told the community is “self-policing.” When it comes to hate speech, Stone doesn’t think his service needs to be as burdened with that as Twitter is — he doesn’t consider the app to be a basic human right. “We can just kick people out if they’re saying mean things. We reserve the right to boot people who are doing hate speech. This is about getting help about every day questions, not about free speech.”

Stone has thought about how to monetize Jelly, but has taken a “wait and see” approach. He wants to prove that the service provides value, and if it does, he will then amplify that offering to justify brands paying for the value. Possible options include a traditional search engine approach when someone shows an express intent in making a purchase (“What are the best socks for running?”) and have a brand get between the user’s desire and answer; promoting real answers from users around that brand; or something else.

While many of us will consider Jelly to be a Q&A service, Stone views it as more of a search engine that doesn’t have hundreds of links and is tailored to today’s technology. If you ask “Where’s the best place to get brunch in San Francisco?” on Google, you’ll likely get an answer, but you will have to parse through hundreds of text links, OpenTable options, and more. But with Jelly you’re throwing a question to the crowd, and it’ll be answered by a supposed expert in that topic.

And Jelly believes that its mission is only helped by the proliferation of voice. “If you think about voice-over UIs like Alexa, Siri, and Cortana, you can’t have 100 million links as your answer to a question,” Stone said. “You need an answer for subjective questions, just like with ‘What’s 4 plus 4.'”

“We want to get to a world where instantly can get you a great answer.”

The app Stone wants, but one that we need?

Jelly certainly has vision, but does it have what it takes to actually succeed as a strong app and appeal to users? Although the company claims it’s “on demand,” it’s technically not, because timing will depend on the availability of an expert — another human being to follow through after receiving a notification. So it could take a minute, 10 minutes, an hour, or a day. Stone said that the more people on the app, the better the experience will be — of course.

The difference between version 1.0 of Jelly and this current form isn’t substantial. Yes, the company has done away with the social network integration and put less emphasis on camera use, but for the most part, the core Jelly experience is the same. If it didn’t work then, will it work now? Stone’s team may think that the updated workflow and user experience can be the thing that helps Jelly be a hit app, but it’s a stretch. Right now, the Jelly app seems to be a bit light on the bells and whistles, and what could ultimately make it worthwhile to the greater masses.

Over the course of Jelly’s various transformations, the company has received some funding. At first, Stone self-funded it to prove that it was a legitimate service. Then he called up Spark Capital before taking more money from Greylock Partners, two firms that Stone knew from his time at Twitter. The exact amount hasn’t been disclosed, but Stone said he took a “modest amount” from outside partners. However, he told us, “If [Jelly] works out, we will raise a bunch of money because we need machine learning persons and powerful back-end engineers.”

Jelly is available now for everyone on iOS, mobile web, and on desktop.