Investors have hammered Facebook’s stock price lately, selling it on growing fears about its ability to make money on mobile.

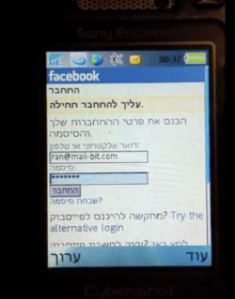

For more concerns about Facebook’s mobile prospects, consider the fate of its chat application on feature phones — those non-smartphones that still make up a majority of the global market.

The app, called “Facebook Chat,” has enjoyed significant uptake since Facebook began offering it almost two years ago. Despite this, the app makes no money. Absolutely none.

Feature phone owners can find the Facebook chat app in the major download stores, from Nokia’s Ovi Store to Getjar. In just 18 months, the app racked up more than 40 million downloads. It has 100,000 new downloads a day.

Feature phone owners can find the Facebook chat app in the major download stores, from Nokia’s Ovi Store to Getjar. In just 18 months, the app racked up more than 40 million downloads. It has 100,000 new downloads a day.

To be sure, Facebook has invested no resources into the site. A third-party company manages it, on limited servers and little development — accessing Facebook APIs. The app’s managers say the app can handle only a limited number of simultaneous connections. Still, monthly active users number 1.4 million.

But here’s the rub. The monetization prospects are so miserable that the app’s external developer, a company called mSonar, may discard it soon because the cost of upkeep may no longer be worth it.

Facebook’s awkward management of the app’s operation, and apparent bait-and-switch with the app’s developer on whether to try advertising or not, or even to allow it, reflect Facebook’s ongoing struggle with how to deal with mobile.

Feature phones, in particular, are a significant challenge for Facebook. Feature phones still make up 76 percent of the mobile market, Facebook is seeing much of its growth in countries where feature phones are popular — places like Indonesia, Nigeria, Mexico, and Pakistan.

VentureBeat learned about the feature phone chat app’s struggle to monetize after interviewing Ran Ben-David, the founder of mSonar, the start-up that built the app for Facebook, and that still controls it. As Ben-David tells it, Facebook contracted with mSonar to distribute the app under the Facebook brand. At the time, Facebook insisted that the app be distributed for free. When Ben-David asked how Facebook planned to help him monetize it, a Facebook executive told him he was confident that the likely huge numbers of downloads would mean it would be easy to make money from advertising. Moreover, Ben-David says, Facebook promised to talk with phone manufacturers, such as Nokia, that might also be interested in paying for the right to pre-embed the app in its new phones.

However, Facebook soon changed its mind and insisted that mSonar not place advertising in the app. This wasn’t too surprising, Ben-David says, because Facebook had long fretted that ads degrade the mobile experience: Better to avoid ads, and spur growth, and then worry about monetizing later. Facebook executives gave regular assurances to Ben-David to keep distributing the app. Ben-David obliged, assuming that Facebook would help, as it had promised.

Ben-David watched as downloads kept growing, but slowly became concerned. The app consistently ranks between No. 1 and No. 5 on the Nokia Ovi store. But the growth is in places like India, and Saudi Arabia, where ads are about a cent per thousand impressions, compared to about 20 cents in the U.S, Ben-David says. Facebook did take pains to introduce Ben-David to its executives in various countries to market the app. Special versions were made for Brazil and Russia. These executives tried to market the app to manufacturers in those countries to help monetize it, but there were no takers.

Every so often, Ben-David would contact Facebook’s US executives, warning them of his growing server and development costs, but no help came. Slowly, Facebook gave up its efforts on Ben-David’s behalf. Finally, more recently, Facebook’s executives told Ben-David he should start searching for manufacturer partners himself and that the company was going to pass on actually licensing or buying the app — citing the app’s low retention numbers, among other things. Ben-David responds that retention levels are suffering in large part because he’s had few resources to develop the app. He also sent Facebook evidence that the app was crashing because of server limitations.

Facebook spokesman Derick Mains said that since the app is controlled by a third-party developer, it’s the app developer’s responsibility to come up with a business model. He wouldn’t comment further on the specific case of the chat app.

Frustrated, Ben-David says Facebook has baited and switched on him — egging him on to build the app and keep distributing it, but then pulling the rug out from under him. He fears he’ll never make money. “Monetizing mobile on Facebook is impossible,” he says. He may soon have to pull the app and drop its 1.4 million active users. He’s still negotiating with Facebook about how to save the app, but says he is giving up hope.

Photo credit: Stephan Geyer/Flickr