One of the sad realities about our super connected digital age is that, while technology makes it easier for us to communicate, it also makes it easier for third parties to snoop on our conversations.

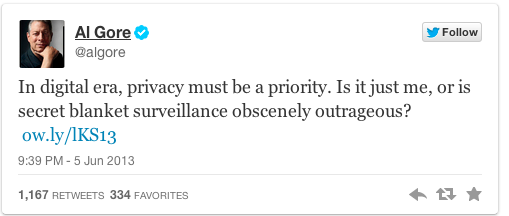

This became painfully clear yesterday when The Guardian reported that the National Security Agency (NSA) has been quietly collecting the call data of Verizon customers since issuing a secret court order to the company back in April. The order, which extends until July, is untargeted, meaning that the NSA can snoop on calls without suspecting anyone of wrongdoing.

The implications of the news are widespread, particularly for journalists horrified at the prospect that the government can use their phone records to identify their sources. (Journalists are also still reeling from the news that the Justice Department obtained two months’ worth of call records from Associated Press reporters. It’s been a rough few weeks.)

The situation is a bit complicated, and the outrage that accompanies these kinds of stories tends to obfuscate what’s actually going on. Here’s a brief overview:

How much of this is actually new?

Quite a lot, but still very little. While these sorts of programs have been suspected for years, this is the first time we’ve gotten such extensive proof of what’s going on — in particular during the Obama administration.

One of the more interesting details about the order is that its April 25th timing coincides with the days after the Boston Marathon bombing.

Also notable is that two senators — Ron Wyden of Oregon and Senator Mark Udall of Colorado — have been warning about these sorts of broad surveillance programs for years. They just couldn’t talk about it directly. “As we see it, there is now a significant gap between what most Americans think the law allows and what the government secretly claims the law allows,” the senators wrote last year.

So is the NSA is snooping on my calls?

Not exactly. Under the Verizon order, the NSA is only gaining access to the so-called “metadata” around your calls — e.g., when you made them, what numbers you made them to, how long the calls lasted, and where they were made from. Getting the actual content of the calls, or even the names or addresses of the callers, would make the surveillance wiretapping, which would be a separate issue, legally.

What can the NSA do with this information?

While the White House is arguing that call metadata isn’t private information — it’s closer to the information on an envelope, they say — that couldn’t be further from the truth. With the right kind of data mining and analysis, the NSA can still learn a lot about you, even it doesn’t know what you’re saying while on a call or who exactly you are.

To use the most basic example, let’s say you make a lot of calls in the evening from one specific location, and you don’t move all that much while on the phone. Chances are that location is your house. Suddenly, that supposedly public information becomes a lot more private.

Still, the NSA maintains that all this information is used for pattern analysis, which should, in theory, allow it to spot suspicious activity. But it’s in the name of security that the government is also getting its hands on a ton of data that it’s never had access to previously. And that should probably scare your pants off.

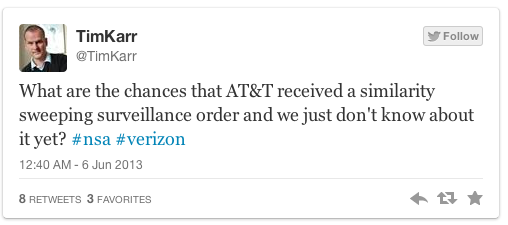

Is Verizon alone?

While its tough to say for sure, it’s hard not to imagine the NSA making similar orders with other big telecom companies like AT&T, Sprint, and T-Mobile. Let’s take the safe route and say that, no, Verizon is not alone on this.

UPDATE: Look’s like that safe route was indeed the right one. Sources told The Wall Street Journal on Thursday that the cell phone records data collection also extends to AT&T and Sprint. Surprise, surprise.

What can I do about this?

Unless you’re willing to give up your smartphone forever, very little. Not only are these programs kept secret, but companies like Verizon have no choice but to abide by them. Moreover, the NSA’s program isn’t technically violating the law; Congress has been approving these sorts of things for years and has repeatedly pressed to keep them secret. As a result, like most things, the solution is clear: Vote out politicians who approve these sorts of programs — assuming you care about this at all.

While there’s a certain defeatism that accompanies news of widespread governmental surveillance, there’s good reason to suspect that this news will stir up more backlash than usual.

Photo: Flickr/Eric Hauser