While its not clear if he even knows about the page, it make Facebook’s efforts in China more complicated. Facebook is already trying to figure out if it should create a special Chinese version of Facebook that the Chinese government would be able to censor.

[aditude-amp id="flyingcarpet" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":93024,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"social,","session":"C"}']Throwing the censorship issue into the limelight: Wen’s page features some criticisms of him and his country, concerning among other things, Tibet protests, environmental issues, and, of course, media censorship.

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and VentureBeat founder Matt Marshall talked briefly at the AllThingsD conference about Zuckerberg’s recent sweeping tour of Asia. China was one of the countries Zuckerberg didn’t visit, he said.

AI Weekly

The must-read newsletter for AI and Big Data industry written by Khari Johnson, Kyle Wiggers, and Seth Colaner.

Included with VentureBeat Insider and VentureBeat VIP memberships.

It may be portentous that the Facebook name sounds like the Chinese phrase, fei si bu ke (非死不可), which translates to “doomed to die” or “bound to die.” Transliterations like this are a challenge of doing business in China (more on that here).

Facebook faces tough competition. Wildly popular Chinese instant message service QQ already has a social network, Qzone. There’s an even closer rival, Xiaonei, a Facebook clone that recently raised $430 million that is already popular on Chinese college campuses. Facebook may not have the right combination of features, some speculate, to appeal to Chinese users.

To compete, though, Facebook has already created a Chinese language version of its site, I hear. It is holding this version back while it figures out the politics. Facebook has been interested in the Chinese market for some time. Facebook has had its Chinese domain, Facebook.cn, registered since March of 2005, China blogger Kaiser Kuo points out. Last year, the company was rumored to be buying an existing Chinese social network.

The booming population of Chinese internet users is a huge opportunity, already estimated to be around 230 million strong and growing fast. What Facebook has done, besides a translation: It has raised $120 million from Hong Kong business mogul Li Ka-Shing, who has also pumped much more money into investments in mainland China.

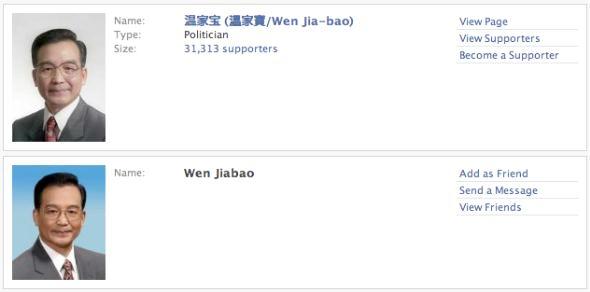

Sample from Wen’s page:

[aditude-amp id="medium1" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":93024,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"social,","session":"C"}']

Sure, Li knows China and its leaders well. The question is, will that be enough of a reason for the government to give Facebook special privileges in avoiding censorship. The government already censors social media sites, like social networks and video-sharing sites.

The Chinese government is likely to view Facebook as a more potent kind of social network. MySpace and other rivals are seen by the government as entertainment sites, not forums for serious dissent (although MySpace, at least, is putting resources into growing in China). Facebook’s focus is on real people having real interactions. It’s being used effectively by US presidential candidates, not to mention protesters in Colombia and other countries.

Facebook’s realness and its still-booming worldwide growth could help the company further differentiate from its China-based rivals. But even these aspects have their own downsides. A government could use a social network to track down national international dissident rings, using a user’s so-called “social graph” of interests and friend relations, contributor David Nordfors pointed out here last year. That’s not going to appeal to everyone.

For the Chinese government, a decision to not censor Facebook would be a fundamental shift in its domestic policy. Meanwhile, for Facebook, creating a censored version would be a big move. Facebook hasn’t — from my understanding — been actively censoring in other countries around the world. That includes many Middle East countries; one result is that Middle Eastern and American college students are having fun playing games and flirting with each other on Facebook in spite of their respective leaders’ wishes.

[aditude-amp id="medium2" targeting='{"env":"staging","page_type":"article","post_id":93024,"post_type":"story","post_chan":"none","tags":null,"ai":false,"category":"none","all_categories":"social,","session":"C"}']

This is clearly a tough call for both parties. China has taken steps, especially in its open approach to dealing with the earthquake disaster, to signal increasing openness to the free flow of information within its borders. Facebook, whether it wants to be or not, is now in a position to find out just how far the government is willing to go.

VentureBeat's mission is to be a digital town square for technical decision-makers to gain knowledge about transformative enterprise technology and transact. Learn More