This post has not been edited by the GamesBeat staff. Opinions by GamesBeat community writers do not necessarily reflect those of the staff.

You've had an exceptionally stressful day. Neglecting household chores, you instead boot up your current game and proceed to play far past your bedtime until your bleary-eyed stare can no longer withstand the captivating glow of the screen.

Unfortunately, you died moments away from an autosave checkpoint or a predesignated save location. An inflexible save system is a prescription for headache — as numerous articles from Bitmob indicate — but at the core of this is our frustration with the concept of losing progress. In fact, we’re so overly concerned with being productive that some of us even feel guilty dicking around and neglecting story missions in open-world titles like Grand Theft Auto.

We’re frustrated because we know what it means to lose progress in most modern games. I dreaded reloading a sequence in Killzone 2’s linearly designed single-player campaign at one particular checkpoint save over and over again. Why? Because I realized that the game forced me to perform the same actions in the same order — repeatedly — to progress further.

I walked the same hallways. I ducked behind the same sandbags. I shot the same enemies in the same sequence. Each reload unfolded almost identically — except for the few moments after my previous death and before my next one. I was bored out of my mind. Only perseverance and trial-and-error deduction got me through to the next section.

But what if we measured progress differently? What if progress meant not driving the narrative or reaching the final stage in a series of carefully crafted playgrounds but instead meant understanding game mechanics? What if progress meant learning to play more proficiently at a deeper level?

Enter the roguelike.

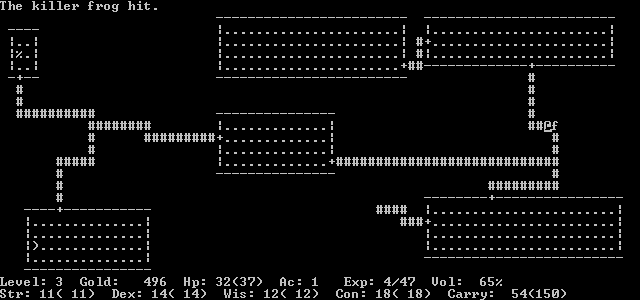

Rogue was the culmination of Michael Toy’s and Glenn Wichman’s efforts to create a graphical appropriation of a text-adventure game, known simply as Adventure, popular on college campuses. Back in 1980, most university computer labs were based on a shared mainframe accessed by a network of dumb terminals that could only display text characters; thus, Rogue broke new ground with its use of ACSII code to represent the game world.

The duo’s seminal title also popularized the dungeon crawler — each level of Rogue is a procedurally generated series of rectangular rooms connected by snaking corridors. The game randomly allocates monsters and treasures for the player to fight and discover throughout the journey. This aspect of content creation brings seemingly infinite replay value and means that no two playthroughs are ever the same.

But the defining features most identified with Rogue are the fragility of your character and the institution of permanent death. When you die in the game, you cannot return to a previous save state. You cannot reclaim your avatar and retry the situation that killed you.

Therefore, progress in Rogue is not progress in the traditional sense. Descending lower in the dungeon and advancing in character levels are secondary to the real meat of the experience: understanding gameplay systems and how they interact. Through experimentation and exploration, which are core design tenets of the genre, you slowly become a better player.

You needn’t build yourself an ancient mainframe to play Rogue, though, which is now available as a browser-based Java game. The genre built by this graphical adventure continues to thrive in small, dedicated corners of the larger gaming community, and I’d like to highlight a few titles on the next page that I’ve played recently.

These are by no means definitive or exhaustive; I hope to pique your interest in others, such as direct inspirations Hack and NetHack, the charming platformer roguelike Spelunky, the intimidatingly ambitious Dwarf Fortress, and the less unforgiving Shiren the Wanderer.

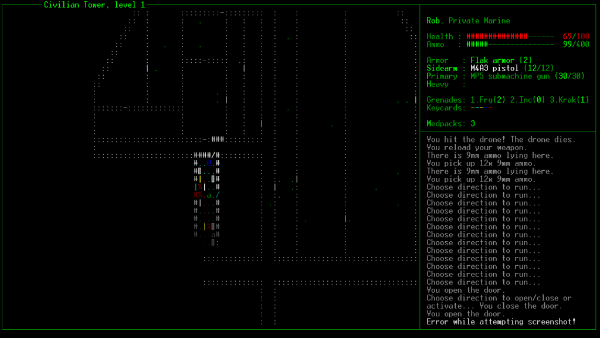

Aliens Roguelike (PC: available here)

One of developer Kornel Kisielewicz’s many roguelikes in a state of perpetual development, such as Doom Roguelike, Diablo Roguelike, and Berserk!, this Aliens variant follows a similar formula. The setting and concept are incredibly focused — a “high-concept game,” if you will — on the motif set forth by the surrealist artist H.R. Giger, Alien film director Ridley Scott, and — of course — James Cameron’s return to the sci-fi horror with Aliens.

You take control of a stranded colonial marine based on those in Cameron's sequel, who finds himself dumped into an unnamed military complex. Your only stated goal is to find and kill the alien queen somewhere in the labyrinth of civilian, military, storage, and other towers that constitute the facility.

Aliens Roguelike builds the tension and atmosphere of what I imagine Rebellion sought with their first Aliens vs. Predator attempt for the Atari Jaguar back in 1994. With gameplay based on exploration, experimentation, and a little bit of luck, I’ve easily put more hours into this than Killzone 2.

Rogue Survivor (PC: available here)

Developer Rogued Jack’s simulation of the zombie apocalypse takes the survivalist aspect of roguelikes to a new plane. Traditionally, you’d gain experience and level up your character by eliminating enemies. In Rogue Survivor, you only increase in strength and ability by enduring a night of undead carnage.

“Dungeon” crawling in this title exists in the exploration of sections of town, which is split into randomly generated districts. To survive, you need to acquire food to satiate your hunger and weapons to defend yourself from not only the recently reanimated, but also biker gangs, a sinister corporation, and the military. You’ll also need to barricade yourself into basements and safe houses in order to get a good night’s sleep while keeping those hunting for your brains at bay.

Dungeon Crawl: Stone Soup (PC: available here)

Stone Soup is an actively developed, open-source roguelike based on Linley Henzell’s 1995 title Dungeon Crawl. And a fully realized tile-set in place of ASCII graphics isn’t the only thing that sets this game apart from the others mentioned here.

Exploration is certainly a central component of Stone Soup, but experimentation plays an even larger role. In Aliens Roguelike, experimentation comes in the form of weapon play versus different alien types. In Rogue Survivor, players experiment with defensive strategies. But in Stone Soup, everything is an experiment.

With 23 different species and 28 different classes to choose from, you’re forced to investigate different playstyles right from the beginning. The game also builds this concept directly into the random loot scattered about in the dungeons. Upon first discovery, scrolls and potions are mysteries. You won’t know what they do until you try them out for yourself.

Despite all this complexity, Stone Soup eases the player into the daunting task to combing the highly diverse, procedurally generated levels of byzantine mazes; long, spiraling corridors; and large, open spaces. A helpful tutorial introduces the controls (which includes full mouse support!), and a hints mode slowly educates the player of more advanced concepts as he uncovers them.

A roguelike reminds me of a cold bottle of Dogfish Head 90-minute Indian pale ale — bitter at first but a wave of sweet, malty flavor washes over your tongue before you’re through.

You will die. A lot. But each death is a lesson that brings you closer to understanding the game merely by playing. Because each new try is random in every way possible, you’ll never feel like you lost traditional game progress. Instead, you’ll enter the next round with another piece of the intricate puzzle solved.

We define a roguelike through the core design tenets of exploration and experimentation. Aliens Roguelike, Rogue Survivor, and Stone Soup all utilize those concepts in different ways to encourage you to think for yourself. With enough experience, you might even be able to predict the outcome of future scenarios on the fly, which brings a satisfactory feeling of accomplishment that few other genres provide. These titles might even be able to shake that consolitis out of you.

Once you swallow that first bitter taste, your eventual victory in the face of seemingly overwhelming odds is that much sweeter — just like a beer enthusiast's slow discovery of quality beverages in lieu of mass-produced, watered-down Miller Lites and Budweisers.